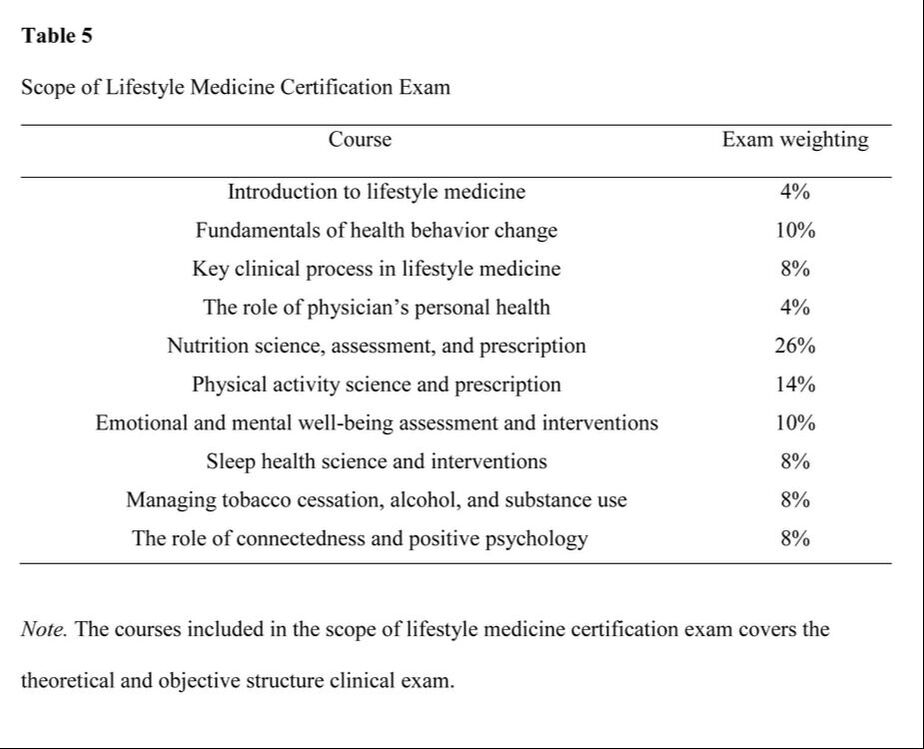

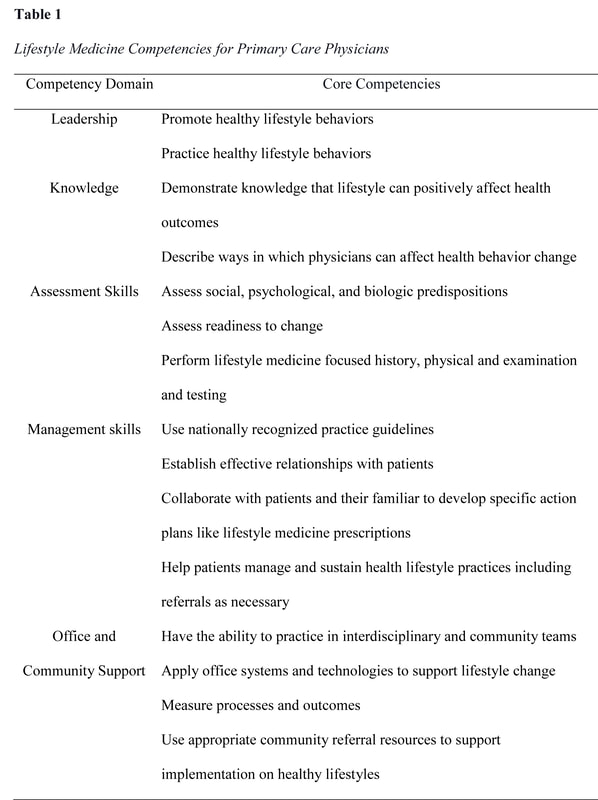

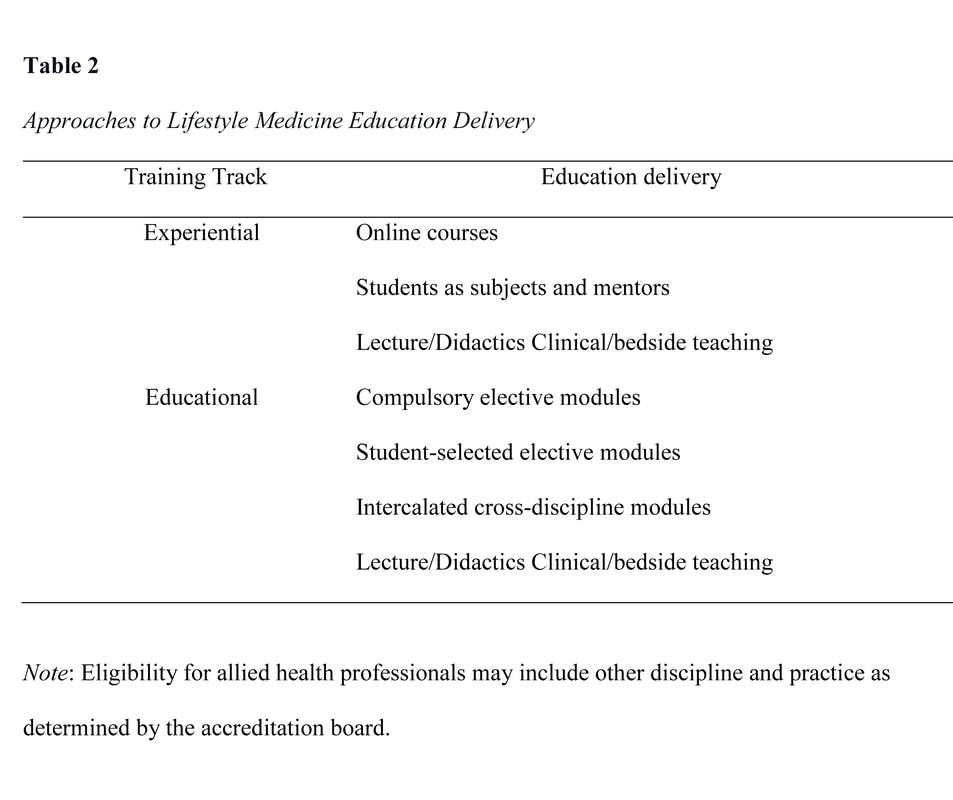

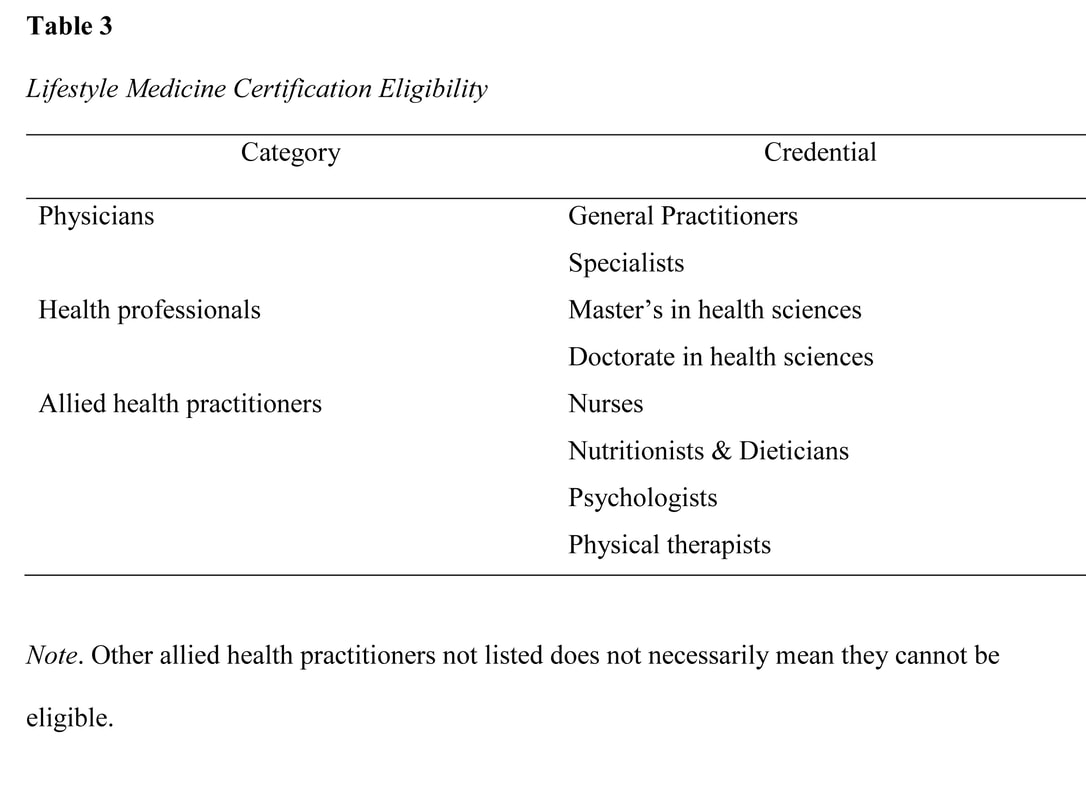

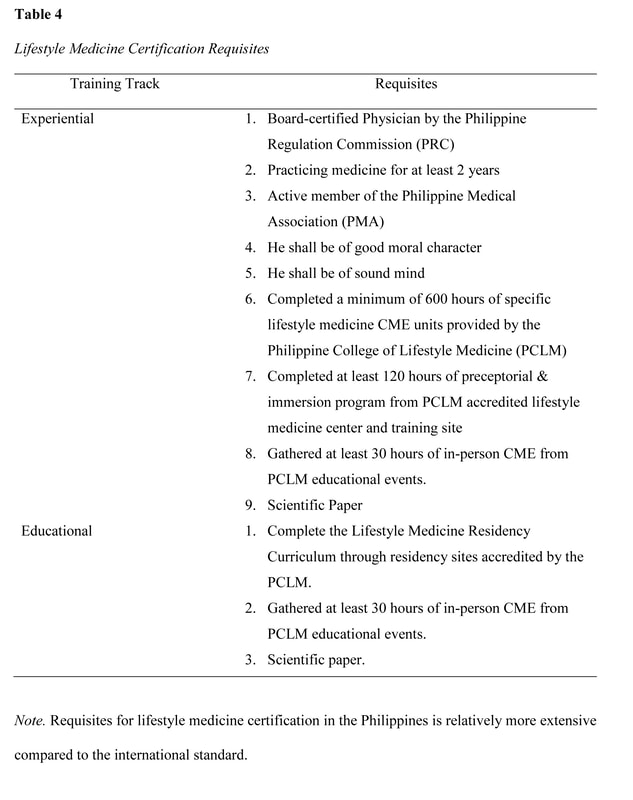

lifestyle medicine education initiaves: intervention for the 21st century epidemiologic transition11/27/2020 Abstract The actual burden of noncommunicable disease has resulted in a huge socioeconomic loss, with a medical system unprepared to address the 21st-century epidemiological transitions disproportionately impacting low-medium income countries. Like any developing country, health care providers in the Philippines are not equipped to implement lifestyle intervention as the primary approach to these chronic conditions despite the repeated emphasis on its role in the clinical practice guidelines. This gap is seemingly due to the long-overdue demand to address the inadequacy of lifestyle medicine education in both medical and interprofessional curricula resulting in poor skills and confidence among prospective health care providers to deliver effective lifestyle intervention to patients. Advancing the early initiatives in integrating lifestyle medicine across all levels of medical education and interprofessional training through various initiated methodologies is therefore proposed as an essential intervention to address the inevitably growing burden. This review explores how socioeconomic factors can influence the development and implementation of lifestyle medicine education in response to the call for medical and interprofessional curricula reformation. Information on the existing lifestyle medicine education programs initiated by several organizations and training institutions that training institutions can adopt in the Philippines will also be provided. The primary initiatives on this effort showed positive outcomes; however, local research on this field is extremely limited to non-existent; thus, much work remains to be done. Keywords: lifestyle medicine education, lifestyle medicine continuing education, lifestyle therapy, lifestyle interventions Background The close association of lifestyle with the pathogenesis of chronic diseases has been established since early times (Bodai et al., 2018). Investigations on a plant-predominant diet (Kim et al., 2019) and active lifestyle (Sheikholeslami et al., 2018) was observed in a population where heart disease and hypertension are almost non-existent (Shaper et al., 2012) in contrast to a modern lifestyle of fast-food consumption and inactivity (Reber et al., 2019 & Salwa et al., 2019). The role of lifestyle changes in the context of a new medical paradigm is repeatedly emphasized in the 21st-century approach to healthcare in line with the epidemiologic transitions and disease patterns (WHO, 2019). Lifestyle interventions can decrease morbidity, mortality, medical costs, and economic loss. Yet, only very few health care providers felt that they are adequately educated and skilled to implement lifestyle therapy in their clinical practice (Trilk et al., 2019). With over 70% of deaths worldwide attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that are lifestyle-related (WHO, 2019), renewed interest has emerged in lifestyle medicine education (Trilk et al., 2019). Many training institutions at different levels of discipline and education are realigning their positions on the role of lifestyle therapy in the medical education continuum (Polak et al., 2015). It is also recently that some medical schools and training institutions have begun to integrate competencies of lifestyle intervention in the training curriculum and bedside teaching (Polak et al., 2014). Lifestyle medicine (LM) provides an evidence-based solution to the non-communicable chronic disease epidemic; however, lifestyle medicine education in medical curricula is minimal to non-existent (Nawaz, et al., 2016). The current trend of public health challenges is directed to socioeconomic variables (WHO, 2019) as significant drivers that can move medical education to integrate LM in the traditional undergraduate medical education (UME) curricula, graduate medical education, and continuing medical education (Polak et al., 2015). Substantive research in medical, social, and behavioral sciences has identified the demand for improving education on lifestyle intervention, including behavior change, nutrition, and physical activity counseling (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). This review explores how socioeconomic factors can influence the development and implementation of LM education in the Philippines. Specific factors include 1) changing trend in health care demand and corresponding economic loss, 2) increasing emphasis on lifestyle therapy as primary approach to chronic disease, 3) inadequacies in LM education among medical students and medical trainees, and 4) limited incumbent LM trained physicians to train prospective health care providers. What is Lifestyle Medicine? Lifestyle medicine is an evidence-based clinical practice that utilizes the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors in patients such as nutrition, physical activity, behavior change, sleep health, tobacco cessation, responsible alcohol use, emotional wellness, and stress reduction for prevention, management, and even reversal of some chronic diseases (ACLM, n.d.). Lifestyle medicine was first used in one of the proceedings of the Brussels symposium in 1989 (Wynder, 1989), and its principles, including plant-predominant diet and active lifestyle have been published in numerous studies since the early times (Strom & Jensen, 1951) to the present (Mozaffarian, 2016). The practice of LM was highlighted and gained attention in the medical industry over the past 2 decades, with the study by Ornish et al. (1998) demonstrating significant reversal of coronary artery disease in patients who had intensive lifestyle modification, including a plant-based diet, active lifestyle, and healthy relationships. Moreover, the INTERHEART study done in 52 countries demonstrate that adopting a healthy lifestyle may prevent 90% of all heart disease (Yusuf, 2005). Another substantive population study revealed that a healthy lifestyle might also prevent strokes, diabetes, and cancers (Ford, 2009). A more recent randomized controlled trial with more than 20,000 population also showed significant improvement in body weight, plasma lipids, and glycemic control in only 18 weeks of dietary intervention. (Mishra et al., 2013). Furthermore, lifestyle intervention may increase survival and decrease mortality in the overweight and obese population that improves each time a new healthy habit is achieved (WHO, 2016). These shreds of evidence consistently revealed the important role of LM as the primary approach to NCDs with highly modifiable lifestyle-related etiology. Behavior Change Theory Underpinning Lifestyle Medicine Lifestyle medicine intervention incorporates elements from several behavior change theories such as the Transtheoretical Model, Health Belief Model, and the Social Cognitive Theory. The basis of lifestyle intervention, however, is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Understanding the underpinnings of lifestyle behaviors will more likely be effective in providing valuable assistance in developing behavior change interventions when based on sound theory. The TPB asserts that the closest determinant of behavior is the intention to perform that behavior driven by intention, formed from attitudes, social norms, and perceived control (Davis, 2015). Lifestyle medicine has a strong educative component to change attitudes toward healthy living and utilize a group setting to foster a healthier social influence and accountability to be more effective for achieving health goals than individual programs. Finally, LM has an intensive intervention nature that demands active involvement to increase the participants’ self-efficacy and perceived control (Gillison, 2015). Noncommunicable Disease Socioeconomic Impact The noncommunicable disease burden in the Philippines has been clearly defined. It has affected the economic status at both household and national level due to the healthcare cost and the loss in patient's productivity. The presence of chronic conditions demands long-term healthcare maintenance costs leading to poverty and socioeconomic status decline. This chronic condition with heightened susceptibility tied to low socioeconomic status (Tomlinson, 2020) is passed from one generation to the next, not only because it runs with the genes but because behavior is also influenced by a psychosocial and familial factor (Philips et al., 2014). The health literacy, attitude, and perception towards the relationship between healthy behaviors and noncommunicable diseases of the parents can be adopted by children and is passed on continuously (Wigen & Wang, 2014). Thus, it is always easy to see the same disease burden with similar behavioral and lifestyle practices among family members from the grandparents to the grandchildren. The noncommunicable disease significantly reduced the economic output in the Philippines, as shown in the findings of the joint report of the United Nations Interagency Task Force on NCDs, the World Health Organization, and the Philippine Department of Health. The NCD burden in the country has gone up to an estimated cost of over PHP 750 billion (US$ 14.5 billion) or about 4.8% of the national gross domestic product. The figure is attributed to direct costs, including healthcare and social security provision. The survey also revealed that the indirect cost has an estimated financial burden of approximately 9 times higher than the direct costs arising from workforce loss and reduced productivity (Figure 1). Thus, highlighting the human and economic cost of NCD burden warrants a highly cost-effective investment in lifestyle intervention packages (Figure 2) and healthcare provider education that will contribute to the country's overall socioeconomic development (WHO, 2019). Finally, this report also emphasize the existing fragmented and overlapping programs resulting to disparities in healthcare provision and overall population health outcome (WHO, 2019). Lifestyle Therapy in the Clinical Practice Guidelines Clinical practice guidelines are intended to use evidence to identify practices that meet patients' needs in most circumstances (Molino, et al., 2016). These guidelines are utilized in the modern definitions of primary care, where the importance of health promotion, disease prevention, and integrated services are emphasized (Carandang et al., 2020). The recently published guidelines for chronic diseases uniformly showed increasing comprehensive emphasis on healthy behaviors and lifestyle therapy as the first line of intervention for the top killer diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. These recommendations consistently call for efficient implementation of lifestyle interventions for successful prevention and management outcomes (Arnett et al., 2019; Garber et al., 2020). One of the most recent guidelines was published by the ACC and AHA that recommends implementing healthy lifestyle interventions throughout life as an essential method to prevent ASCVD (Arnett et al., 2019). Another recently published guideline was the 2019 comprehensive type 2 diabetes (T2D) management guideline developed by the consensus of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE). These guidelines provide practical instruction for physicians to manage the patient as a whole person, including the spectrum of risks and complications. The first founding principle of the AACE/ACC 2019 algorithm, like the ACC/AHA algorithm, is lifestyle therapy recommended for all patients with diabetes. The guidelines urge that lifestyle therapy begins with motivational interviewing techniques, nutrition counseling, and education for initial visits and each follow-up visit. It was also emphasized that lifestyle therapy should be continued even when concurrent pharmacotherapy is prescribed (Arnett et al., 2019 & Garber et al., 2020). The treatment guideline recommendations consistently emphasize lifestyle behavior assessment and intervention as an initial approach to address all aspects of a patient's modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors. Then it should be followed by the assessment of estimated future risk before deciding on whether there is a need for pharmacotherapy or not. These treatment guidelines recommend that clinicians focus their attention on counseling and motivating patients to maintain healthy lifestyle for life, even if medications are prescribed in the end. And because the recommended guideline is comprehensive that needs various expertise and skills, a collaborative team approach is needed (Garber et al., 2020; Arnett et al., 2019). The evolving challenge, however, is not only in the efficiency of clinical implementation of these guidelines by trained healthcare providers. More importantly, the adherence to the recommendations that can be enhanced by a comprehensive patient-centered collaborative approach that is strongly focused on lifestyle optimization (Kim et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2013). Inadequacy in Lifestyle Medicine Education Similar to many low-and middle-income countries facing epidemiological transitions, health professionals in the Philippines are encountering more socially diverse patients with chronic conditions (WHO, 2019) where management demands the supposed unprecedented collaborative care using lifestyle interventions as the primary approach to prevention and management (Lacagnina, et al., 2018; Clarke & Hauser 2016). These rapid demographic and epidemiological transitions brought about by environmental and behavioral threats perpetuate inequities as the application of the 20th-century medical education strategies are unfit to address the 21st-century health care challenges (Frenk et al., 2010; Gordon & Hans, 2012). The Lancet Commission Report argued that education needed transformation to meet health systems' needs (Frenk et al., 2010). In response to this international call, the Technical Committee for Medical Education (TCME) proposed action plans on rationalizing medical education in the Philippines and approved by the Commission on Higher Education (CHED). This transformation action plan is directed towards addressing the mismatch between medical graduates' education and training and their roles as health professionals in the health system (CHED, 2016 & Reyes, 2018). Thus, an opportune time to also integrate lifestyle medicine education in the medical and interprofessional curricula. In the United States, the Bipartisan Policy Center has called for options to improve medical education and training, emphasizing lifestyle interventions such as nutrition and physical activity. Together with the American College of Sports Medicine and Alliance for Healthier Generation, the Bipartisan Policy Center described efforts to address ongoing knowledge and skills gap on topics traditionally given limited emphasis in the traditional medical school curricula and training programs (BPC, 2014). Despite the central role of dietary intake and physical activity (PA) in a lifestyle intervention for chronic diseases, evidence revealed that nutrition education and PA counseling largely escapes clinical training and remains incorporated as a preclinical context of basic science courses (Neuendorfl et al., 2020 & Shuval et al., 2017 ). A recent systematic review on nutrition education in medical school curricula shows nutrition is insufficiently incorporated into medical education (Adams et al., 2015), regardless of country, setting, or medical education level (Crowley et al., 2019). In the Philippines, although basic nutrition is a required component of medical school curricula (CHE, 2016), nutrition education is mostly focused on malnutrition (UNSSCN, 2017), and medical nutrition therapy is confined to subspecialties (Senarath, et al., 2019) such as gastroenterology and endocrinology (Reber et al., 2019). More recently, a review of 109 studies found that in the curricula used to educate medical trainees to implement behavioral change counseling on patients for healthier lifestyles, PA was the least addressed subject compared to nutrition, smoking, alcohol, and substance use (Dacey et al., 2014) despite active campaign on physical inactivity (Sheikholeslami et al., 2018). Similar surveys and studies for review on nutrition and PA counseling for chronic conditions locally are very limited. Training the Trainers One of the major constraints in implementing LM education in training institutions for prospective health care providers is the limited incumbent trainers (Kaye et al., 2018). It is clearly impossible to educate future health care providers and thus build up a body of specialists in a particular field if there are no appropriately trained teachers with which to start. This is a common initial challenge to overcome to advance a new field of practice (Trilk et al., 2019). Another constraint is the physician’s attitudes towards personal health practices. Physicians are also reluctant to train prospective healthcare providers to counsel on behaviors that they do not personally pursue (Harkin et al., 2019). To address the challenge of trainers ill-equipped to deliver LM education, initiatives from several organizations and institutions have gained thrust toward filling this need (Wattanapisit, et al., 2018). Continuing medical education (CME) programs is one the most feasible way for trainers to acquire experiential education in lifestyle medicine (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). The CME program in lifestyle medicine is currently offered by many institutions initiated by the American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM) and the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM). Presently, there are several accredited CME programs that will satisfy the requisites to qualify for the certification examination in lifestyle medicine offered in multiple sites worldwide (IBLM, n.d.). Curriculum Development and Training Implementation Because of the existing inadequacy of lifestyle medicine intervention in medical education, prospective healthcare providers and even trainers turn to alternative training sources through web-based research, conferences, webinars, peer-reviewed scientific journals, lifestyle medicine-related documentaries, and textbooks. This track may not be the traditional education pathway, but it has led to the development of LM training programs currently offered in different levels of medical and interprofessional education (Caines et al., 2018). Because of these initiatives, transitions, and paradigm shifts in medical and interprofessional education, lifestyle medicine was advanced as a new specialty recognized by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AMMC, 2018). The American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM) hosted a blue-ribbon panel meeting to define the practice and establish the 15 core competencies in lifestyle medicine for primary care physicians (Table 1). These physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine were consequently published in the Journal of American Medical Association in 2010 (Lianov & Johnson, 2010). Subsequently, the American Medical Association (AMA) passed Resolution 959 that called for all physicians to acquire and apply the 15 clinical competencies of lifestyle medicine and offer LM interventions as the primary mode of preventing and treating chronic disease. The resolution asserted the needed reformation in the medical education curriculum to respond to the inadequacy of knowledge and skills to approach the changing trend in noncommunicable disease in the United States (Trilk et al., 2019). The United States has also pioneered training activities, curricular development, and credentialing in LM through the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM), the first national professional society for clinicians specializing in the use of lifestyle interventions to treat and manage disease. The ACLM proposed the mechanism for lifestyle medicine education and credentialing and has conducted annual conference since 2011, released publications since 2008, conduct education programs and credentialing through the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine (ABLM) and the International Board of Lifestyle Medicine (IBLM) since 2017 (ACLM, n.d.). Several organizations have also emerged with a uniform objective of advancing LM education and delivery. The Institute of Lifestyle Medicine (ILM), founded in 2007 at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and Harvard Medical School, created training programs for healthcare professionals and conducted research demonstrating lifestyle medicine's efficacy for national adoption (ILM, n.d.). Another significant organization is the Lifestyle Medicine Education Collaborative founded in 2013 involving medical schools, professional associations, government agencies, accreditation agencies, and national assessment boards to provide guidance, tools, and resources to advance the adoption and implementation of lifestyle medicine curricula throughout medical education (LMed, n.d.). Other institutions who have developed a curriculum and offered lifestyle medicine education in different levels of medical and interprofessional training include the Avondale University in Australia (AUC, n.d.), Lithuanian University of Health and Sciences (LUHS, n.d.), and the Adventist University of the Philippines (AUP, n.d.). Putting aside the immediate challenge of insufficient faculty and trainers, various approaches to implementing LM education have been used (Table 2): compulsory or student-selected elective modules, intercalated cross-discipline modules (Nawaz et al., 2016), lecture-based teaching, clinical/bedside teaching, online courses (Polak et al., 2017), and courses where the students are actively involved in the assessments and teaching (Kaye et al., 2018). The different approaches vary in their degree of reliance on faculty-led teaching including choices on elective courses on lifestyle interventions such as culinary medicine (Razavi, 2015). Described below are the current programs initiated by organizations and academic institutions world-wide. Undergraduate Education Interprofessional training on lifestyle therapy can be provided at all healthcare education levels (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). The Metropolitan State University of Denver offered the first undergraduate education in lifestyle medicine (Bachelor of Science Major in Lifestyle Medicine) in the United States (Toffelson et al., 2019) that provides cultural competence themes, interdisciplinary collaboration, and whole-person health care (MSUD, n.d.). In the Philippines, the Central Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine also offered the Bachelor of Science in Health, Fitness, and Lifestyle Management and produced graduates; however, the program was eventually closed (CPU, n.d.). Interprofessional training in LM can also be initiated in several existing undergraduate curricula, including Public Health, Exercise and Sports Science, Nursing, Nutrition and Dietetics, Physical Therapy, and Psychology offered by many universities all over the Philippines. Graduate Education There are several pioneering universities offering lifestyle medicine in master’s and a doctorate degree in many different parts of the world, including the 1.5 years master’s degree in Lithuanian University (Lithuanian University, n.d.), the 2 years graduate diploma in Avondale University in Australia (AUC, n.d.). In addition, the Adventist University of the Philippines is the only academic institution in the country that is currently offering the 2 years Master’s degree in Public Health Major in Lifestyle Medicine, which started in 2018 (AUP, n.d.). These academic institutions had initiated another interprofessional education track in lifestyle medicine producing graduates that can provide lifestyle intervention in the space of public health. Undergraduate Medical Education As described previously, the Institute of Lifestyle Medicine (ILM) led a collaborative of essential stakeholders through the LMEd Collaborative to include Lifestyle Medicine competencies as a formal segment in the medical school curricula. This initial effort resulted in a variety of lifestyle medicine courses currently being offered in medical schools, including the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, the first medical school in the U.S. to incorporate lifestyle medicine in all 4 years of undergraduate medical education (USC, n.d.). In the Philippines, the Adventist University of the Philippines College of Medicine is the only medical school that includes a dedicated curriculum in lifestyle medicine interventions such as nutrition assessment and prescription, physical activity science, and lifestyle medicine coaching in all year levels (AUP, n.d.). The increasing number of lifestyle medicine certified trainers the country will be advantageous for medical schools to leverage the existing gap in the curriculum. Graduate Medical Education The Loma Linda University Health initiated the first lifestyle medicine residency and fellowship training in close collaboration with the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (LLHU, n.d.). There are currently 8 sites where lifestyle medicine is integrated as a dual-track in the regular residency training programs such as family medicine, internal medicine, and preventive medicine. The fellowship training was also formalized by the Loma Linda University Health that meets the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine educational pathway requirements (ACLM, n.d.). There are two sites in the Philippines where residency and fellowship training in lifestyle medicine is proposed to be integrated with Family and Community Medicine training programs. The 2 beta sites have an existing lifestyle medicine facility managed and operated by board-certified lifestyle medicine physicians. This is a continuing effort of the PCLM, Adventist Medical Center Bacolod, and Antique Medical Center. While family medicine is the primary track for lifestyle medicine training implementation, it is equally relevant to incorporate lifestyle medicine in other specialty training, including internal medicine residency and fellowship programs. The growing number of LM certified physicians in the Philippines is a promising potential to produce qualified trainers that can augment and advance LM residency and fellowship training. Continuing Medical Education Early studies have already established the effectiveness of continuing medical education (CME) programs designed to educate practicing physicians through the provision of current clinical practice information, including preventive, therapeutic, and diagnostic interventions (Marinopoulos, et al., 2007). Although few publications describe LM CME programs with varied objectives, methodology, duration, and participants, the ACPM and the ACLM initiated CME programs and subsequently followed by several LM organizations and academic institutions worldwide. The LM CME programs are offered as an effective approach to the perception of barriers to LM practices among physicians in an alternative education track (Dacey et al., 2012). These programs ranged in length, from 1 hour to 600 hours of training. Some CME program was designed to provide advanced education to trainers and faculties (ILM, n.d.), while others are tailored to improve management of specific health conditions such as obesity and diabetes through intensive therapeutic lifestyle change programs (PCLM, n.d.). The PCLM is the only organization providing LM CME programs for physicians and allied health professionals since 2018 in the Philippines, but as LM acquired increasing appreciation in both the academe and medical industry, LM-related topics are often incorporated with CME programs in diverse platforms. Lifestyle Medicine Certification in the Philippines In 2018, the lifestyle medicine certification exam was initiated by the International Board of Lifestyle Medicine in the Philippines. With the continued growth and advancement in LM education and practice in the country, the PCLM, through the Commission on Specialty Board Examinations in Lifestyle Medicine maintains standards for the assessment and credentialing of health care providers (Table 3) in Lifestyle Medicine with the objective to govern the standardization and regulation of lifestyle medicine practice in the Philippines. The Certification signifies specialized knowledge in the practice of lifestyle medicine and distinguishes health care provider as having achieved competency in lifestyle medicine. Candidates for the certification exam can either seek national or national and international board certification. A candidate can be eligible through 2 tracts such as experiential and education pathways with specific requisites (Table 4). The examination is given on the dates and in places determined by the Board with certain provisions, including the theoretical and Objective Structured Clinical Examination (Table 5).  Research Gaps, Trends and Future of Lifestyle Medicine Education in the Philippines Lifestyle medicine was born in the Philippines when the Coronary Heart Improvement Program, now called Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP), a community-based intensive therapeutic lifestyle change (ITLC) program (Morton et al., 2014) for chronic disease, was introduced in 2009. The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine (PCLM) was organized by the pioneers in 2015 and gained recognition by the government agencies, academe, and medical industry in the past few years (PCLM, n.d.). However, there is a minimal publication on local studies on CHIP as one of the banner programs of Lifestyle Medicine in the Philippines, while publication on PCLM initiatives is limited to reports. Among the first efforts in the country's LM campaign was the conduct of the first Lifestyle Medicine Conference for government-employed physicians and health committee chair in 2017 initiated by the Asian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM), the PCLM, and the Philippine Councilors League (PCL) Legislative Academy. This event had the goal to introduce Lifestyle Medicine to primary health care providers and policymakers in the country (PCLM, n.d.). This initiative generated the creation of the first LM driven City Ordinance sponsored by the former Bacolod City Committee on Health Chair, Councilor Em Ang promulgating Healthy Lifestyle Programs at the local government level (Panay News 2019). The Agricultural Training Institute 7, headed by center director Dr. Caroline Daquio is another government agency that adopted LM programs, particularly culinary medicine that was cascaded to the agency's beneficiaries (e.g., farmers, teachers, high school students) in partnership with the local government and department of education of Bohol (PIA, 2020). To ensure the standard delivery of the increasing number of LM education programs, the PCLM Committee on Education created policies and procedures for accreditation of training institutions, training programs, and training providers to provide lifestyle medicine education programs. These policies will determine the quality of LM education delivered across the medical and interprofessional curricula. Although PCLM is still in its early stages, LM education continues to evolve in many different implementation levels. The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine has identified 5 strategic areas in the development of lifestyle medicine curricula: 1) provide high-quality curricular material using a hybrid platform with in-person and online delivery, 2) solicit the support of the Association of Philippine Medical Colleges, Commission on Higher Education, Department of Health, and training hospitals to advocate and implement lifestyle medicine curricula in medical and interprofessional education, 3) establish an impact on government policies through increased awareness that will encourage adoption of lifestyle intervention in primary health care delivery to address the current socioeconomic burden brought about by NCDs, 4) develop and conduct an evaluation on student knowledge and practice, trainer efficacy, and program effectiveness, and 5) secure quality and integrity of credentialing lifestyle medicine providers at par with the global standard of practice. The PCLM is clearly the prime mover of the LM education implementation in the country. The organization has been recognized by the Lifestyle Medicine Global Alliance with level four membership, leading the LM movement in Asia. PCLM has conducted annual conferences, postgraduate courses, scientific sessions, CME programs, and facilitated credentialing of LM health care providers in the country since 2018. Currently, PCLM is moving its way to be accredited by the Philippine Medical Association (PMA) and the Philippine Regulation Commission (PRC) through the Philippine Academy of Family Physicians (PAFP) as an affiliate medical society. Moreover, PCLM is equally heading towards advancing LM education with other medical disciplines and interprofessional practices to promote effective collaborative team management (PCLM, n.d.). The pioneering cohort of certified LM healthcare providers is instrumental to LM education provision that will potentially address the long overdue demand in relation to the current NCD crisis and heightened socioeconomic burden. Conclusion Both the healthcare system and providers continue to face barriers in providing a solution to the NCD related burden globally. Lifestyle medicine is the evidence-based and logical response to this global epidemiological transition challenge. There is a long-overdue demand within this effort, and local publications for review is limited or non-existent. The medical curriculum reform must include lifestyle medicine education to resolve the existing inadequacies in prospective healthcare providers. To achieve the goal of implementing lifestyle medicine education among health professionals, 5 basic strategies should be implemented at all levels of training. However, to make long-term progress with this issue, local research is recommended to investigate the present socioeconomic forces that should be considered and addressed in the broader context to establish how it is perceived and accepted by the medical and interprofessional academe, medical profession, legislators, and the public. In turn, health care providers will become more competent to make meaningful contributions to medical education and improve healthcare delivery directed to address the 21st-century epidemiological transition and the double burden of disease. The inceptive initiatives toward this goal have demonstrated optimistic results through various methodologies, constructive collaboration, structured implementation, and, more importantly, positive clinical outcomes, though much work remains to be done. References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the metanalysis.

2 Comments

|

AuthorMechelle Acero Palma, MD Archives

August 2021

Categories |

|

Working Hours

Monday to Friday: 8:00am to 5:00pm Online course: 24/7 |

The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine is an Affiliate Specialty Society of the Philippine Medical Association under the division of the Philippine Academy of Family Physicians

RSS Feed

RSS Feed