POSITION PAPER OF THE PCLM ON THE VACCINATION PROGRAM AND THE USE OF IVERMECTIN FOR COVID-19 CASES8/6/2021

0 Comments

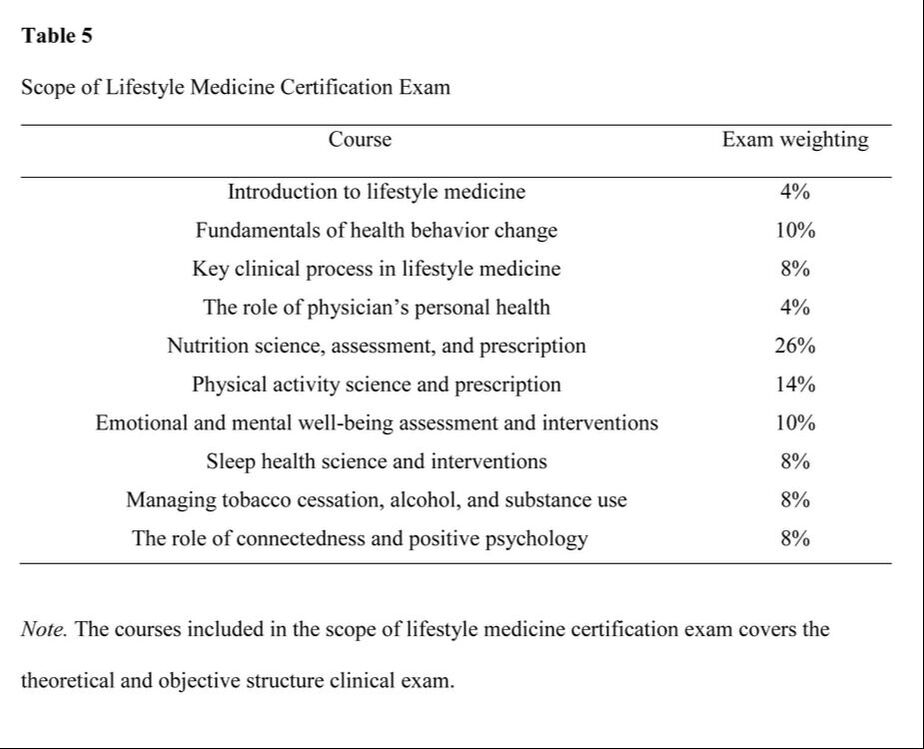

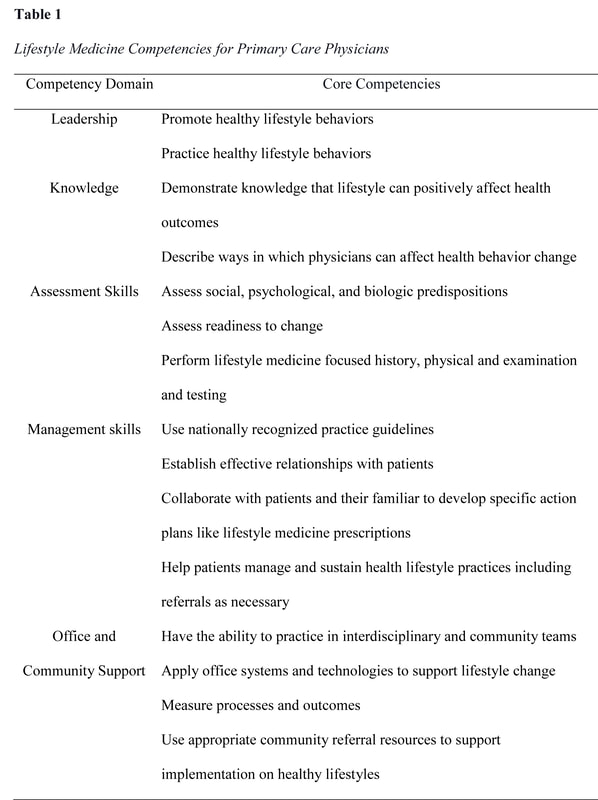

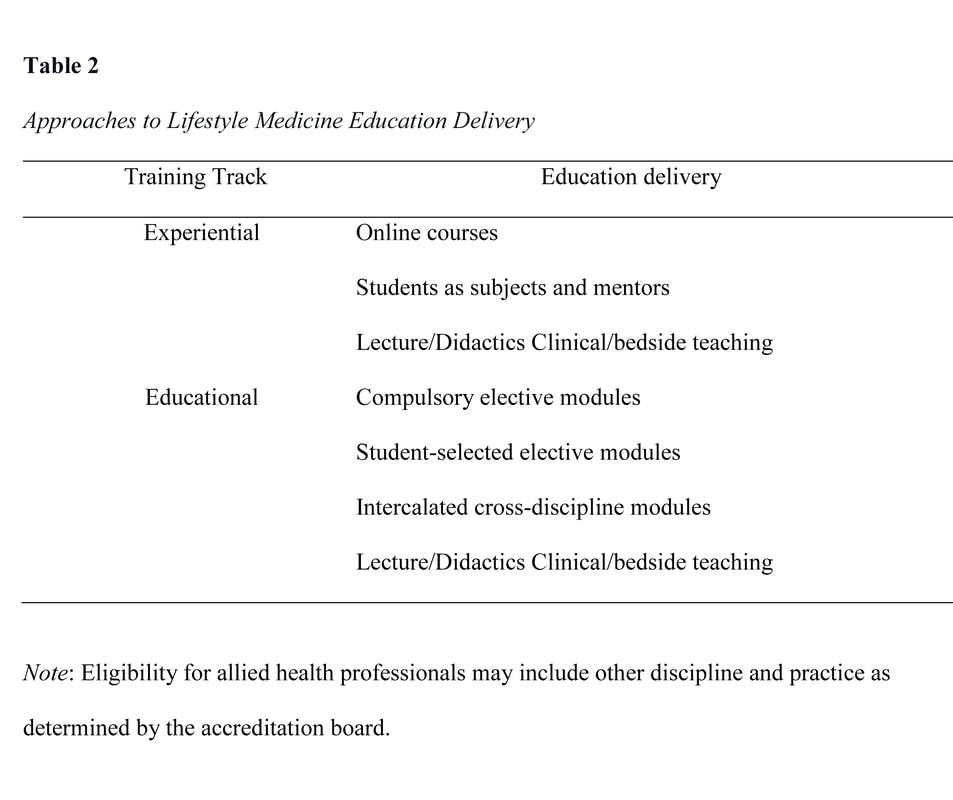

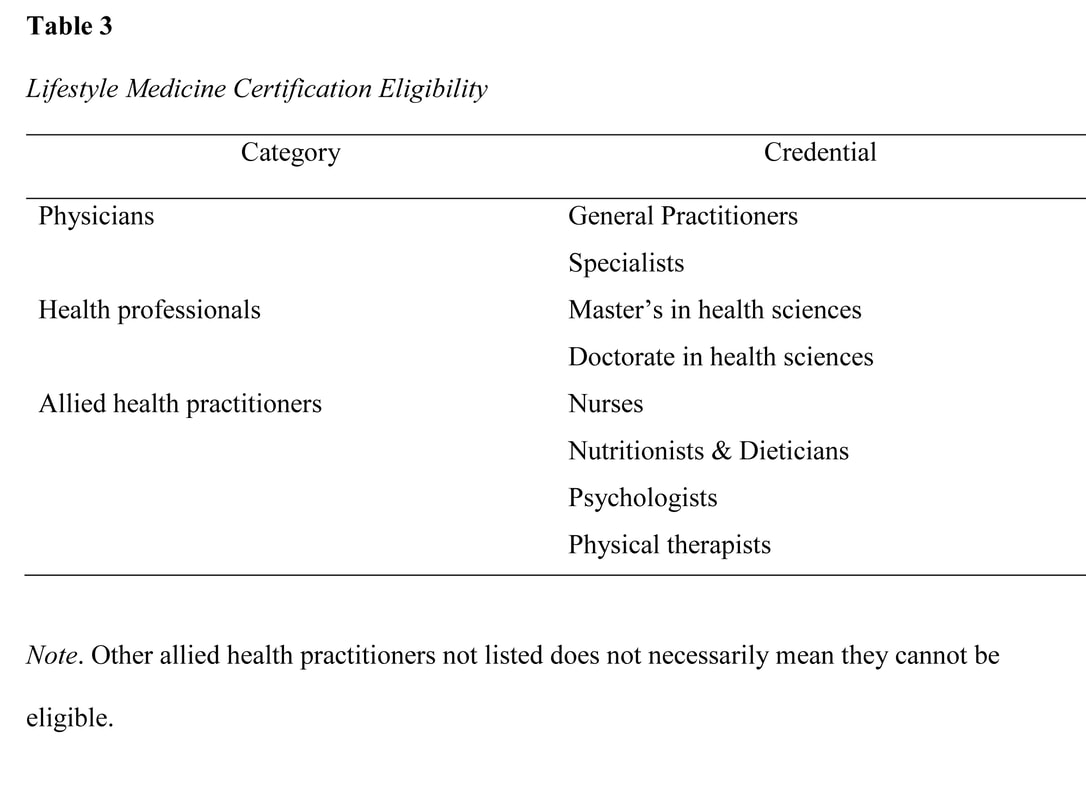

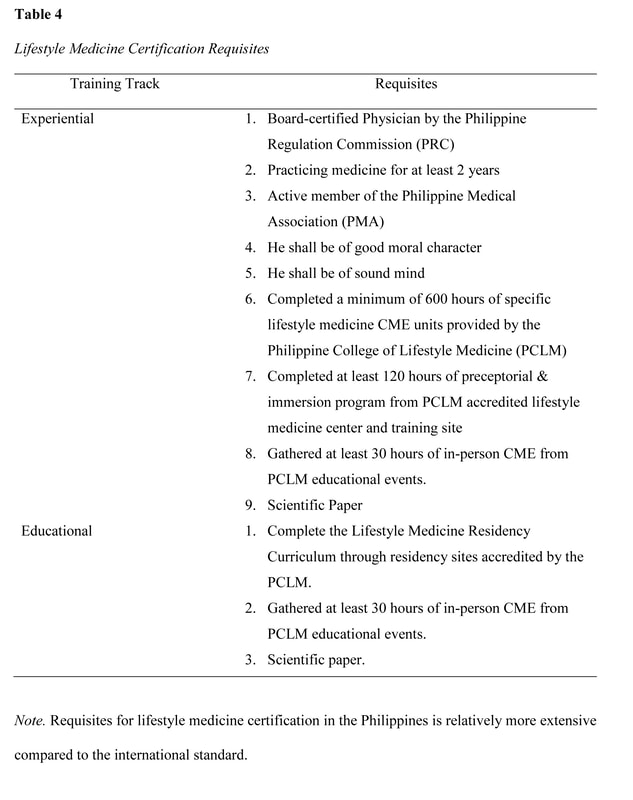

lifestyle medicine education initiaves: intervention for the 21st century epidemiologic transition11/27/2020 Abstract The actual burden of noncommunicable disease has resulted in a huge socioeconomic loss, with a medical system unprepared to address the 21st-century epidemiological transitions disproportionately impacting low-medium income countries. Like any developing country, health care providers in the Philippines are not equipped to implement lifestyle intervention as the primary approach to these chronic conditions despite the repeated emphasis on its role in the clinical practice guidelines. This gap is seemingly due to the long-overdue demand to address the inadequacy of lifestyle medicine education in both medical and interprofessional curricula resulting in poor skills and confidence among prospective health care providers to deliver effective lifestyle intervention to patients. Advancing the early initiatives in integrating lifestyle medicine across all levels of medical education and interprofessional training through various initiated methodologies is therefore proposed as an essential intervention to address the inevitably growing burden. This review explores how socioeconomic factors can influence the development and implementation of lifestyle medicine education in response to the call for medical and interprofessional curricula reformation. Information on the existing lifestyle medicine education programs initiated by several organizations and training institutions that training institutions can adopt in the Philippines will also be provided. The primary initiatives on this effort showed positive outcomes; however, local research on this field is extremely limited to non-existent; thus, much work remains to be done. Keywords: lifestyle medicine education, lifestyle medicine continuing education, lifestyle therapy, lifestyle interventions Background The close association of lifestyle with the pathogenesis of chronic diseases has been established since early times (Bodai et al., 2018). Investigations on a plant-predominant diet (Kim et al., 2019) and active lifestyle (Sheikholeslami et al., 2018) was observed in a population where heart disease and hypertension are almost non-existent (Shaper et al., 2012) in contrast to a modern lifestyle of fast-food consumption and inactivity (Reber et al., 2019 & Salwa et al., 2019). The role of lifestyle changes in the context of a new medical paradigm is repeatedly emphasized in the 21st-century approach to healthcare in line with the epidemiologic transitions and disease patterns (WHO, 2019). Lifestyle interventions can decrease morbidity, mortality, medical costs, and economic loss. Yet, only very few health care providers felt that they are adequately educated and skilled to implement lifestyle therapy in their clinical practice (Trilk et al., 2019). With over 70% of deaths worldwide attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that are lifestyle-related (WHO, 2019), renewed interest has emerged in lifestyle medicine education (Trilk et al., 2019). Many training institutions at different levels of discipline and education are realigning their positions on the role of lifestyle therapy in the medical education continuum (Polak et al., 2015). It is also recently that some medical schools and training institutions have begun to integrate competencies of lifestyle intervention in the training curriculum and bedside teaching (Polak et al., 2014). Lifestyle medicine (LM) provides an evidence-based solution to the non-communicable chronic disease epidemic; however, lifestyle medicine education in medical curricula is minimal to non-existent (Nawaz, et al., 2016). The current trend of public health challenges is directed to socioeconomic variables (WHO, 2019) as significant drivers that can move medical education to integrate LM in the traditional undergraduate medical education (UME) curricula, graduate medical education, and continuing medical education (Polak et al., 2015). Substantive research in medical, social, and behavioral sciences has identified the demand for improving education on lifestyle intervention, including behavior change, nutrition, and physical activity counseling (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). This review explores how socioeconomic factors can influence the development and implementation of LM education in the Philippines. Specific factors include 1) changing trend in health care demand and corresponding economic loss, 2) increasing emphasis on lifestyle therapy as primary approach to chronic disease, 3) inadequacies in LM education among medical students and medical trainees, and 4) limited incumbent LM trained physicians to train prospective health care providers. What is Lifestyle Medicine? Lifestyle medicine is an evidence-based clinical practice that utilizes the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors in patients such as nutrition, physical activity, behavior change, sleep health, tobacco cessation, responsible alcohol use, emotional wellness, and stress reduction for prevention, management, and even reversal of some chronic diseases (ACLM, n.d.). Lifestyle medicine was first used in one of the proceedings of the Brussels symposium in 1989 (Wynder, 1989), and its principles, including plant-predominant diet and active lifestyle have been published in numerous studies since the early times (Strom & Jensen, 1951) to the present (Mozaffarian, 2016). The practice of LM was highlighted and gained attention in the medical industry over the past 2 decades, with the study by Ornish et al. (1998) demonstrating significant reversal of coronary artery disease in patients who had intensive lifestyle modification, including a plant-based diet, active lifestyle, and healthy relationships. Moreover, the INTERHEART study done in 52 countries demonstrate that adopting a healthy lifestyle may prevent 90% of all heart disease (Yusuf, 2005). Another substantive population study revealed that a healthy lifestyle might also prevent strokes, diabetes, and cancers (Ford, 2009). A more recent randomized controlled trial with more than 20,000 population also showed significant improvement in body weight, plasma lipids, and glycemic control in only 18 weeks of dietary intervention. (Mishra et al., 2013). Furthermore, lifestyle intervention may increase survival and decrease mortality in the overweight and obese population that improves each time a new healthy habit is achieved (WHO, 2016). These shreds of evidence consistently revealed the important role of LM as the primary approach to NCDs with highly modifiable lifestyle-related etiology. Behavior Change Theory Underpinning Lifestyle Medicine Lifestyle medicine intervention incorporates elements from several behavior change theories such as the Transtheoretical Model, Health Belief Model, and the Social Cognitive Theory. The basis of lifestyle intervention, however, is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Understanding the underpinnings of lifestyle behaviors will more likely be effective in providing valuable assistance in developing behavior change interventions when based on sound theory. The TPB asserts that the closest determinant of behavior is the intention to perform that behavior driven by intention, formed from attitudes, social norms, and perceived control (Davis, 2015). Lifestyle medicine has a strong educative component to change attitudes toward healthy living and utilize a group setting to foster a healthier social influence and accountability to be more effective for achieving health goals than individual programs. Finally, LM has an intensive intervention nature that demands active involvement to increase the participants’ self-efficacy and perceived control (Gillison, 2015). Noncommunicable Disease Socioeconomic Impact The noncommunicable disease burden in the Philippines has been clearly defined. It has affected the economic status at both household and national level due to the healthcare cost and the loss in patient's productivity. The presence of chronic conditions demands long-term healthcare maintenance costs leading to poverty and socioeconomic status decline. This chronic condition with heightened susceptibility tied to low socioeconomic status (Tomlinson, 2020) is passed from one generation to the next, not only because it runs with the genes but because behavior is also influenced by a psychosocial and familial factor (Philips et al., 2014). The health literacy, attitude, and perception towards the relationship between healthy behaviors and noncommunicable diseases of the parents can be adopted by children and is passed on continuously (Wigen & Wang, 2014). Thus, it is always easy to see the same disease burden with similar behavioral and lifestyle practices among family members from the grandparents to the grandchildren. The noncommunicable disease significantly reduced the economic output in the Philippines, as shown in the findings of the joint report of the United Nations Interagency Task Force on NCDs, the World Health Organization, and the Philippine Department of Health. The NCD burden in the country has gone up to an estimated cost of over PHP 750 billion (US$ 14.5 billion) or about 4.8% of the national gross domestic product. The figure is attributed to direct costs, including healthcare and social security provision. The survey also revealed that the indirect cost has an estimated financial burden of approximately 9 times higher than the direct costs arising from workforce loss and reduced productivity (Figure 1). Thus, highlighting the human and economic cost of NCD burden warrants a highly cost-effective investment in lifestyle intervention packages (Figure 2) and healthcare provider education that will contribute to the country's overall socioeconomic development (WHO, 2019). Finally, this report also emphasize the existing fragmented and overlapping programs resulting to disparities in healthcare provision and overall population health outcome (WHO, 2019). Lifestyle Therapy in the Clinical Practice Guidelines Clinical practice guidelines are intended to use evidence to identify practices that meet patients' needs in most circumstances (Molino, et al., 2016). These guidelines are utilized in the modern definitions of primary care, where the importance of health promotion, disease prevention, and integrated services are emphasized (Carandang et al., 2020). The recently published guidelines for chronic diseases uniformly showed increasing comprehensive emphasis on healthy behaviors and lifestyle therapy as the first line of intervention for the top killer diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. These recommendations consistently call for efficient implementation of lifestyle interventions for successful prevention and management outcomes (Arnett et al., 2019; Garber et al., 2020). One of the most recent guidelines was published by the ACC and AHA that recommends implementing healthy lifestyle interventions throughout life as an essential method to prevent ASCVD (Arnett et al., 2019). Another recently published guideline was the 2019 comprehensive type 2 diabetes (T2D) management guideline developed by the consensus of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE). These guidelines provide practical instruction for physicians to manage the patient as a whole person, including the spectrum of risks and complications. The first founding principle of the AACE/ACC 2019 algorithm, like the ACC/AHA algorithm, is lifestyle therapy recommended for all patients with diabetes. The guidelines urge that lifestyle therapy begins with motivational interviewing techniques, nutrition counseling, and education for initial visits and each follow-up visit. It was also emphasized that lifestyle therapy should be continued even when concurrent pharmacotherapy is prescribed (Arnett et al., 2019 & Garber et al., 2020). The treatment guideline recommendations consistently emphasize lifestyle behavior assessment and intervention as an initial approach to address all aspects of a patient's modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors. Then it should be followed by the assessment of estimated future risk before deciding on whether there is a need for pharmacotherapy or not. These treatment guidelines recommend that clinicians focus their attention on counseling and motivating patients to maintain healthy lifestyle for life, even if medications are prescribed in the end. And because the recommended guideline is comprehensive that needs various expertise and skills, a collaborative team approach is needed (Garber et al., 2020; Arnett et al., 2019). The evolving challenge, however, is not only in the efficiency of clinical implementation of these guidelines by trained healthcare providers. More importantly, the adherence to the recommendations that can be enhanced by a comprehensive patient-centered collaborative approach that is strongly focused on lifestyle optimization (Kim et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2013). Inadequacy in Lifestyle Medicine Education Similar to many low-and middle-income countries facing epidemiological transitions, health professionals in the Philippines are encountering more socially diverse patients with chronic conditions (WHO, 2019) where management demands the supposed unprecedented collaborative care using lifestyle interventions as the primary approach to prevention and management (Lacagnina, et al., 2018; Clarke & Hauser 2016). These rapid demographic and epidemiological transitions brought about by environmental and behavioral threats perpetuate inequities as the application of the 20th-century medical education strategies are unfit to address the 21st-century health care challenges (Frenk et al., 2010; Gordon & Hans, 2012). The Lancet Commission Report argued that education needed transformation to meet health systems' needs (Frenk et al., 2010). In response to this international call, the Technical Committee for Medical Education (TCME) proposed action plans on rationalizing medical education in the Philippines and approved by the Commission on Higher Education (CHED). This transformation action plan is directed towards addressing the mismatch between medical graduates' education and training and their roles as health professionals in the health system (CHED, 2016 & Reyes, 2018). Thus, an opportune time to also integrate lifestyle medicine education in the medical and interprofessional curricula. In the United States, the Bipartisan Policy Center has called for options to improve medical education and training, emphasizing lifestyle interventions such as nutrition and physical activity. Together with the American College of Sports Medicine and Alliance for Healthier Generation, the Bipartisan Policy Center described efforts to address ongoing knowledge and skills gap on topics traditionally given limited emphasis in the traditional medical school curricula and training programs (BPC, 2014). Despite the central role of dietary intake and physical activity (PA) in a lifestyle intervention for chronic diseases, evidence revealed that nutrition education and PA counseling largely escapes clinical training and remains incorporated as a preclinical context of basic science courses (Neuendorfl et al., 2020 & Shuval et al., 2017 ). A recent systematic review on nutrition education in medical school curricula shows nutrition is insufficiently incorporated into medical education (Adams et al., 2015), regardless of country, setting, or medical education level (Crowley et al., 2019). In the Philippines, although basic nutrition is a required component of medical school curricula (CHE, 2016), nutrition education is mostly focused on malnutrition (UNSSCN, 2017), and medical nutrition therapy is confined to subspecialties (Senarath, et al., 2019) such as gastroenterology and endocrinology (Reber et al., 2019). More recently, a review of 109 studies found that in the curricula used to educate medical trainees to implement behavioral change counseling on patients for healthier lifestyles, PA was the least addressed subject compared to nutrition, smoking, alcohol, and substance use (Dacey et al., 2014) despite active campaign on physical inactivity (Sheikholeslami et al., 2018). Similar surveys and studies for review on nutrition and PA counseling for chronic conditions locally are very limited. Training the Trainers One of the major constraints in implementing LM education in training institutions for prospective health care providers is the limited incumbent trainers (Kaye et al., 2018). It is clearly impossible to educate future health care providers and thus build up a body of specialists in a particular field if there are no appropriately trained teachers with which to start. This is a common initial challenge to overcome to advance a new field of practice (Trilk et al., 2019). Another constraint is the physician’s attitudes towards personal health practices. Physicians are also reluctant to train prospective healthcare providers to counsel on behaviors that they do not personally pursue (Harkin et al., 2019). To address the challenge of trainers ill-equipped to deliver LM education, initiatives from several organizations and institutions have gained thrust toward filling this need (Wattanapisit, et al., 2018). Continuing medical education (CME) programs is one the most feasible way for trainers to acquire experiential education in lifestyle medicine (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). The CME program in lifestyle medicine is currently offered by many institutions initiated by the American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM) and the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM). Presently, there are several accredited CME programs that will satisfy the requisites to qualify for the certification examination in lifestyle medicine offered in multiple sites worldwide (IBLM, n.d.). Curriculum Development and Training Implementation Because of the existing inadequacy of lifestyle medicine intervention in medical education, prospective healthcare providers and even trainers turn to alternative training sources through web-based research, conferences, webinars, peer-reviewed scientific journals, lifestyle medicine-related documentaries, and textbooks. This track may not be the traditional education pathway, but it has led to the development of LM training programs currently offered in different levels of medical and interprofessional education (Caines et al., 2018). Because of these initiatives, transitions, and paradigm shifts in medical and interprofessional education, lifestyle medicine was advanced as a new specialty recognized by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AMMC, 2018). The American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM) hosted a blue-ribbon panel meeting to define the practice and establish the 15 core competencies in lifestyle medicine for primary care physicians (Table 1). These physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine were consequently published in the Journal of American Medical Association in 2010 (Lianov & Johnson, 2010). Subsequently, the American Medical Association (AMA) passed Resolution 959 that called for all physicians to acquire and apply the 15 clinical competencies of lifestyle medicine and offer LM interventions as the primary mode of preventing and treating chronic disease. The resolution asserted the needed reformation in the medical education curriculum to respond to the inadequacy of knowledge and skills to approach the changing trend in noncommunicable disease in the United States (Trilk et al., 2019). The United States has also pioneered training activities, curricular development, and credentialing in LM through the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM), the first national professional society for clinicians specializing in the use of lifestyle interventions to treat and manage disease. The ACLM proposed the mechanism for lifestyle medicine education and credentialing and has conducted annual conference since 2011, released publications since 2008, conduct education programs and credentialing through the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine (ABLM) and the International Board of Lifestyle Medicine (IBLM) since 2017 (ACLM, n.d.). Several organizations have also emerged with a uniform objective of advancing LM education and delivery. The Institute of Lifestyle Medicine (ILM), founded in 2007 at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and Harvard Medical School, created training programs for healthcare professionals and conducted research demonstrating lifestyle medicine's efficacy for national adoption (ILM, n.d.). Another significant organization is the Lifestyle Medicine Education Collaborative founded in 2013 involving medical schools, professional associations, government agencies, accreditation agencies, and national assessment boards to provide guidance, tools, and resources to advance the adoption and implementation of lifestyle medicine curricula throughout medical education (LMed, n.d.). Other institutions who have developed a curriculum and offered lifestyle medicine education in different levels of medical and interprofessional training include the Avondale University in Australia (AUC, n.d.), Lithuanian University of Health and Sciences (LUHS, n.d.), and the Adventist University of the Philippines (AUP, n.d.). Putting aside the immediate challenge of insufficient faculty and trainers, various approaches to implementing LM education have been used (Table 2): compulsory or student-selected elective modules, intercalated cross-discipline modules (Nawaz et al., 2016), lecture-based teaching, clinical/bedside teaching, online courses (Polak et al., 2017), and courses where the students are actively involved in the assessments and teaching (Kaye et al., 2018). The different approaches vary in their degree of reliance on faculty-led teaching including choices on elective courses on lifestyle interventions such as culinary medicine (Razavi, 2015). Described below are the current programs initiated by organizations and academic institutions world-wide. Undergraduate Education Interprofessional training on lifestyle therapy can be provided at all healthcare education levels (Mondala & Sannidhi, 2019). The Metropolitan State University of Denver offered the first undergraduate education in lifestyle medicine (Bachelor of Science Major in Lifestyle Medicine) in the United States (Toffelson et al., 2019) that provides cultural competence themes, interdisciplinary collaboration, and whole-person health care (MSUD, n.d.). In the Philippines, the Central Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine also offered the Bachelor of Science in Health, Fitness, and Lifestyle Management and produced graduates; however, the program was eventually closed (CPU, n.d.). Interprofessional training in LM can also be initiated in several existing undergraduate curricula, including Public Health, Exercise and Sports Science, Nursing, Nutrition and Dietetics, Physical Therapy, and Psychology offered by many universities all over the Philippines. Graduate Education There are several pioneering universities offering lifestyle medicine in master’s and a doctorate degree in many different parts of the world, including the 1.5 years master’s degree in Lithuanian University (Lithuanian University, n.d.), the 2 years graduate diploma in Avondale University in Australia (AUC, n.d.). In addition, the Adventist University of the Philippines is the only academic institution in the country that is currently offering the 2 years Master’s degree in Public Health Major in Lifestyle Medicine, which started in 2018 (AUP, n.d.). These academic institutions had initiated another interprofessional education track in lifestyle medicine producing graduates that can provide lifestyle intervention in the space of public health. Undergraduate Medical Education As described previously, the Institute of Lifestyle Medicine (ILM) led a collaborative of essential stakeholders through the LMEd Collaborative to include Lifestyle Medicine competencies as a formal segment in the medical school curricula. This initial effort resulted in a variety of lifestyle medicine courses currently being offered in medical schools, including the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, the first medical school in the U.S. to incorporate lifestyle medicine in all 4 years of undergraduate medical education (USC, n.d.). In the Philippines, the Adventist University of the Philippines College of Medicine is the only medical school that includes a dedicated curriculum in lifestyle medicine interventions such as nutrition assessment and prescription, physical activity science, and lifestyle medicine coaching in all year levels (AUP, n.d.). The increasing number of lifestyle medicine certified trainers the country will be advantageous for medical schools to leverage the existing gap in the curriculum. Graduate Medical Education The Loma Linda University Health initiated the first lifestyle medicine residency and fellowship training in close collaboration with the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (LLHU, n.d.). There are currently 8 sites where lifestyle medicine is integrated as a dual-track in the regular residency training programs such as family medicine, internal medicine, and preventive medicine. The fellowship training was also formalized by the Loma Linda University Health that meets the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine educational pathway requirements (ACLM, n.d.). There are two sites in the Philippines where residency and fellowship training in lifestyle medicine is proposed to be integrated with Family and Community Medicine training programs. The 2 beta sites have an existing lifestyle medicine facility managed and operated by board-certified lifestyle medicine physicians. This is a continuing effort of the PCLM, Adventist Medical Center Bacolod, and Antique Medical Center. While family medicine is the primary track for lifestyle medicine training implementation, it is equally relevant to incorporate lifestyle medicine in other specialty training, including internal medicine residency and fellowship programs. The growing number of LM certified physicians in the Philippines is a promising potential to produce qualified trainers that can augment and advance LM residency and fellowship training. Continuing Medical Education Early studies have already established the effectiveness of continuing medical education (CME) programs designed to educate practicing physicians through the provision of current clinical practice information, including preventive, therapeutic, and diagnostic interventions (Marinopoulos, et al., 2007). Although few publications describe LM CME programs with varied objectives, methodology, duration, and participants, the ACPM and the ACLM initiated CME programs and subsequently followed by several LM organizations and academic institutions worldwide. The LM CME programs are offered as an effective approach to the perception of barriers to LM practices among physicians in an alternative education track (Dacey et al., 2012). These programs ranged in length, from 1 hour to 600 hours of training. Some CME program was designed to provide advanced education to trainers and faculties (ILM, n.d.), while others are tailored to improve management of specific health conditions such as obesity and diabetes through intensive therapeutic lifestyle change programs (PCLM, n.d.). The PCLM is the only organization providing LM CME programs for physicians and allied health professionals since 2018 in the Philippines, but as LM acquired increasing appreciation in both the academe and medical industry, LM-related topics are often incorporated with CME programs in diverse platforms. Lifestyle Medicine Certification in the Philippines In 2018, the lifestyle medicine certification exam was initiated by the International Board of Lifestyle Medicine in the Philippines. With the continued growth and advancement in LM education and practice in the country, the PCLM, through the Commission on Specialty Board Examinations in Lifestyle Medicine maintains standards for the assessment and credentialing of health care providers (Table 3) in Lifestyle Medicine with the objective to govern the standardization and regulation of lifestyle medicine practice in the Philippines. The Certification signifies specialized knowledge in the practice of lifestyle medicine and distinguishes health care provider as having achieved competency in lifestyle medicine. Candidates for the certification exam can either seek national or national and international board certification. A candidate can be eligible through 2 tracts such as experiential and education pathways with specific requisites (Table 4). The examination is given on the dates and in places determined by the Board with certain provisions, including the theoretical and Objective Structured Clinical Examination (Table 5).  Research Gaps, Trends and Future of Lifestyle Medicine Education in the Philippines Lifestyle medicine was born in the Philippines when the Coronary Heart Improvement Program, now called Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP), a community-based intensive therapeutic lifestyle change (ITLC) program (Morton et al., 2014) for chronic disease, was introduced in 2009. The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine (PCLM) was organized by the pioneers in 2015 and gained recognition by the government agencies, academe, and medical industry in the past few years (PCLM, n.d.). However, there is a minimal publication on local studies on CHIP as one of the banner programs of Lifestyle Medicine in the Philippines, while publication on PCLM initiatives is limited to reports. Among the first efforts in the country's LM campaign was the conduct of the first Lifestyle Medicine Conference for government-employed physicians and health committee chair in 2017 initiated by the Asian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM), the PCLM, and the Philippine Councilors League (PCL) Legislative Academy. This event had the goal to introduce Lifestyle Medicine to primary health care providers and policymakers in the country (PCLM, n.d.). This initiative generated the creation of the first LM driven City Ordinance sponsored by the former Bacolod City Committee on Health Chair, Councilor Em Ang promulgating Healthy Lifestyle Programs at the local government level (Panay News 2019). The Agricultural Training Institute 7, headed by center director Dr. Caroline Daquio is another government agency that adopted LM programs, particularly culinary medicine that was cascaded to the agency's beneficiaries (e.g., farmers, teachers, high school students) in partnership with the local government and department of education of Bohol (PIA, 2020). To ensure the standard delivery of the increasing number of LM education programs, the PCLM Committee on Education created policies and procedures for accreditation of training institutions, training programs, and training providers to provide lifestyle medicine education programs. These policies will determine the quality of LM education delivered across the medical and interprofessional curricula. Although PCLM is still in its early stages, LM education continues to evolve in many different implementation levels. The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine has identified 5 strategic areas in the development of lifestyle medicine curricula: 1) provide high-quality curricular material using a hybrid platform with in-person and online delivery, 2) solicit the support of the Association of Philippine Medical Colleges, Commission on Higher Education, Department of Health, and training hospitals to advocate and implement lifestyle medicine curricula in medical and interprofessional education, 3) establish an impact on government policies through increased awareness that will encourage adoption of lifestyle intervention in primary health care delivery to address the current socioeconomic burden brought about by NCDs, 4) develop and conduct an evaluation on student knowledge and practice, trainer efficacy, and program effectiveness, and 5) secure quality and integrity of credentialing lifestyle medicine providers at par with the global standard of practice. The PCLM is clearly the prime mover of the LM education implementation in the country. The organization has been recognized by the Lifestyle Medicine Global Alliance with level four membership, leading the LM movement in Asia. PCLM has conducted annual conferences, postgraduate courses, scientific sessions, CME programs, and facilitated credentialing of LM health care providers in the country since 2018. Currently, PCLM is moving its way to be accredited by the Philippine Medical Association (PMA) and the Philippine Regulation Commission (PRC) through the Philippine Academy of Family Physicians (PAFP) as an affiliate medical society. Moreover, PCLM is equally heading towards advancing LM education with other medical disciplines and interprofessional practices to promote effective collaborative team management (PCLM, n.d.). The pioneering cohort of certified LM healthcare providers is instrumental to LM education provision that will potentially address the long overdue demand in relation to the current NCD crisis and heightened socioeconomic burden. Conclusion Both the healthcare system and providers continue to face barriers in providing a solution to the NCD related burden globally. Lifestyle medicine is the evidence-based and logical response to this global epidemiological transition challenge. There is a long-overdue demand within this effort, and local publications for review is limited or non-existent. The medical curriculum reform must include lifestyle medicine education to resolve the existing inadequacies in prospective healthcare providers. To achieve the goal of implementing lifestyle medicine education among health professionals, 5 basic strategies should be implemented at all levels of training. However, to make long-term progress with this issue, local research is recommended to investigate the present socioeconomic forces that should be considered and addressed in the broader context to establish how it is perceived and accepted by the medical and interprofessional academe, medical profession, legislators, and the public. In turn, health care providers will become more competent to make meaningful contributions to medical education and improve healthcare delivery directed to address the 21st-century epidemiological transition and the double burden of disease. The inceptive initiatives toward this goal have demonstrated optimistic results through various methodologies, constructive collaboration, structured implementation, and, more importantly, positive clinical outcomes, though much work remains to be done. References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the metanalysis.

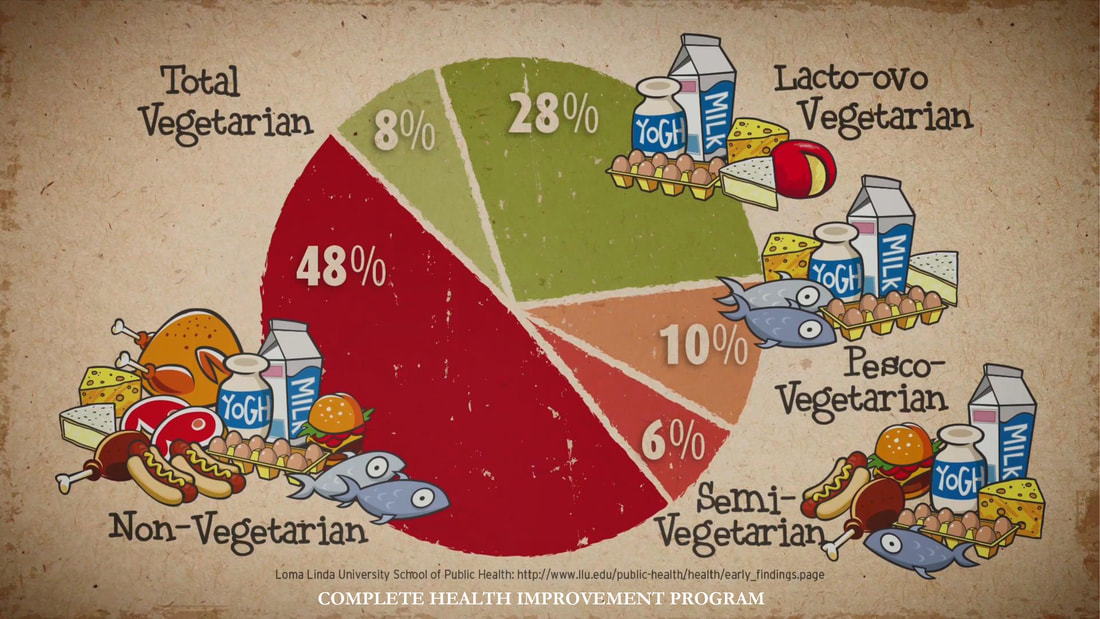

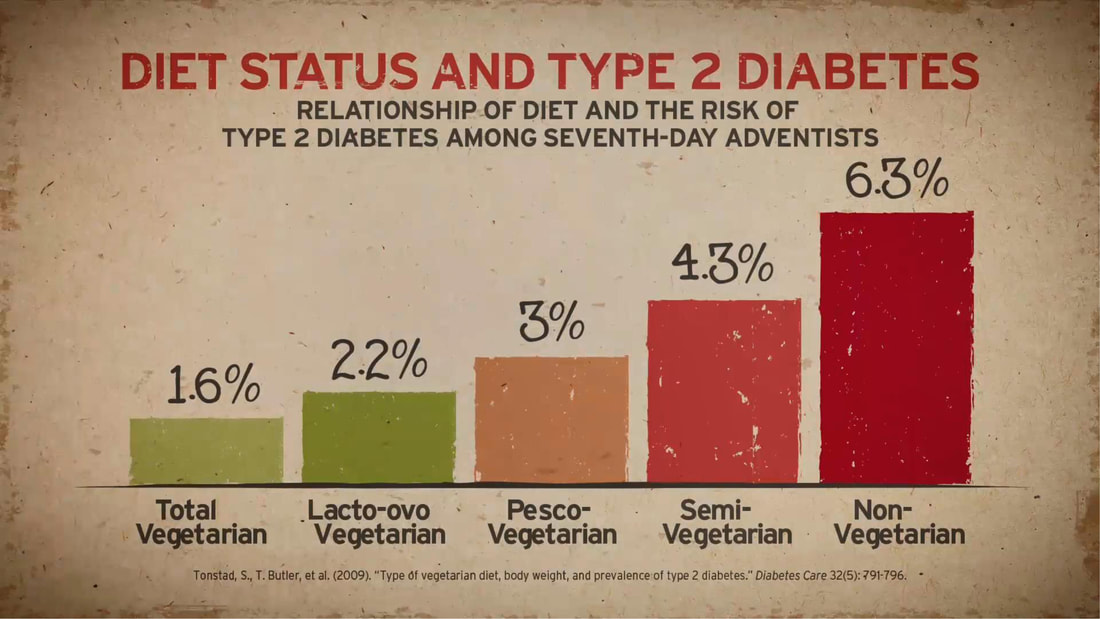

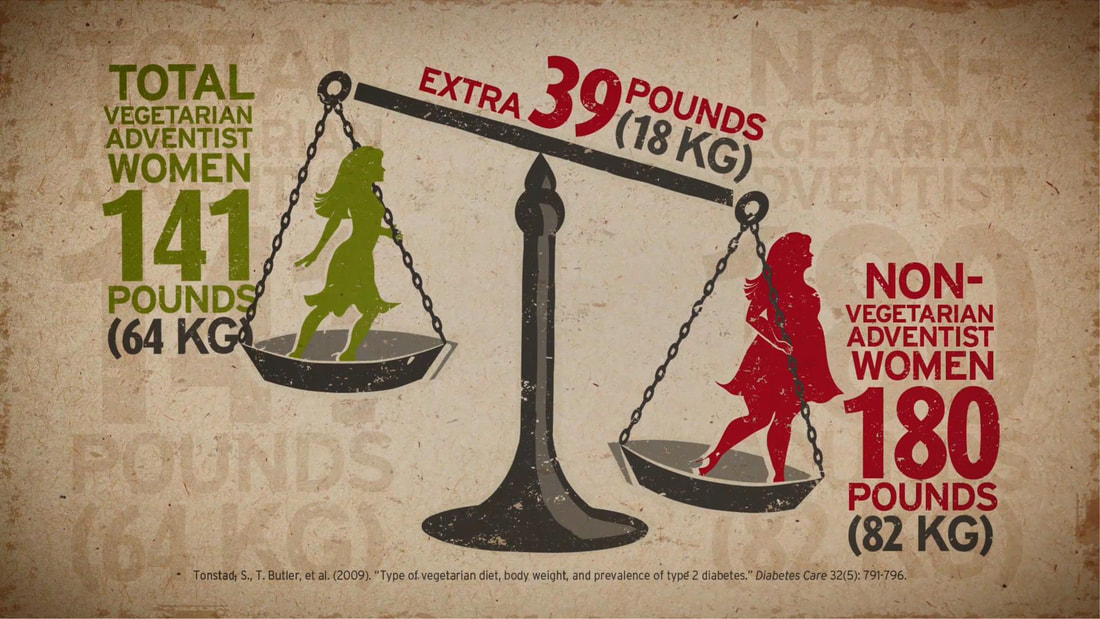

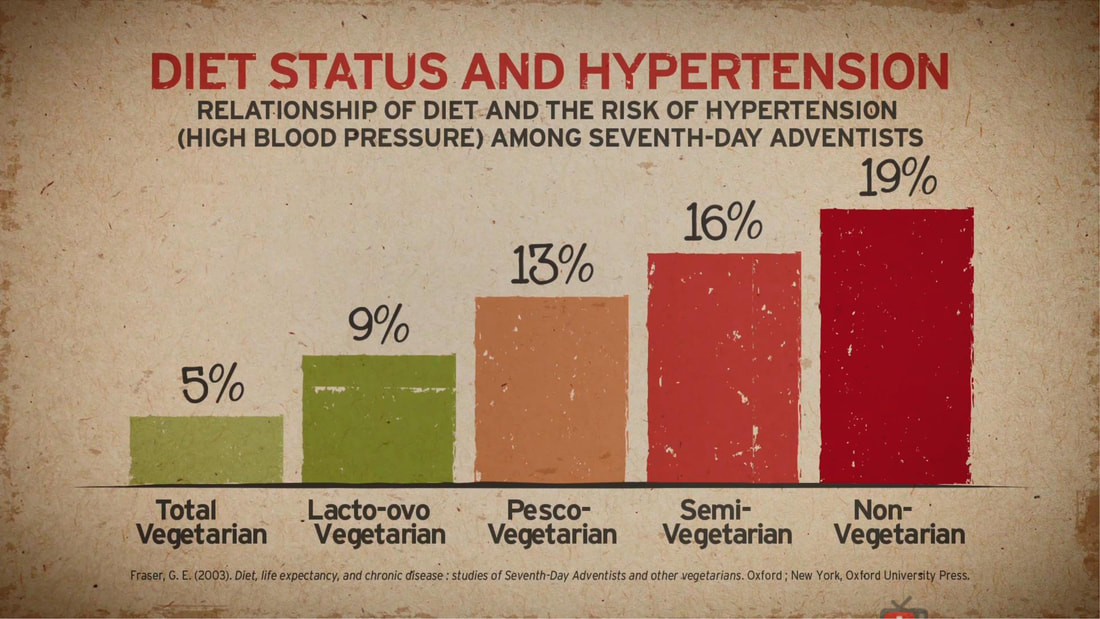

Adventist Health Studies (AHS) is a series of long-term medical research with the objective of establishing the link between lifestyle, diet, disease risk and mortality. Two studies involving 24,000 and 34,000 Seventh Day Adventists in California were conducted over the last 40 years. Researcher's attention was caught by this religious group because of their relatively lower risk of certain disease compared to other Americans.

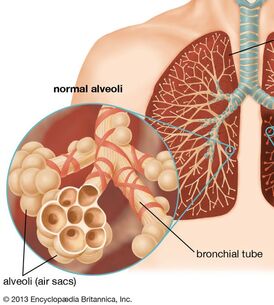

These studies served as dietary reference among Lifestyle Medicine Practitioners globally. It has also been the subject in the National Geographic Article "Longevity: The Secrets of a Long Life." Both studies show the role of dietary behaviors in the development of chronic disease. The more a person stick to a whole food, plant-based diet, the lower the disease risk and mortality. UPDATED MARCH 18, 2020 I MECHELLE ACERO-PALMA, MD The majority of the world's population is now getting acquainted with COVID-19 and its fatality to every affected person and the community at large. The health sector is exhausting all its capacity to provide care for infected people. Multiple collaborations of several government agencies are creating and implementing strategies to address every emerging concern. The media industry is giving its best effort to provide information and updates from authorities to the grassroots. But one potential preventive measure and strategy underemphasized by most media reports and campaigns include evidence-based LIFESTYLE INTERVENTION. A proven measure that anyone can implement to boost immune response may effectively address the need to decrease susceptibility and vulnerability to develop the critical condition due to COVID-19. The real frontliners are the people who are supposed to be educated of their responsibility of taking charge of their health and exhausting any possible resources and capacity to live healthfully and maintain an excellent immune function. There is no clear assurance that COVID-19 will be totally eradicated as it constantly mutates. Early studies are showing possibilities that it will be here to stay. Hence, the best mindset to develop is getting our body ready whenever we contract the virus at any given time. We will be discussing some salient points that each one should understand so we can have the advantage of preventing the disease from spreading and, most importantly, getting our cells ready to combat the viral invasion. WHAT IS NOVEL CORONAVIRUS? We should know the enemy. It is called Novel because it's a new Respiratory disease. We've seen and heard many names such as Coronavirus, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and SARS. This is an RNA virus that can reproduce, and on its surface is a capsule with spikes forming a crown that's why it's called Coronavirus. In 2019 this Coronavirus created a disease outbreak in China, where it has gotten the name COVID-19. Then the World Health Organization created the official scientific name SARS-CoV-2 because this is the second generation daughter virus of SARS6. Scientists were given a heads up in 2003 to understand the nature of this family of Coronavirus. With the advent of genomics, they were able to understand how contagious the Coronavirus is. And sadly, due to mutations, it has allowed SARS-CoV-2 to become a thousand times more infective than SARS. Hence, a community quarantine was implemented in almost all countries affected to lessen the spread of infection. HOW CORONAVIRUS INFECT HUMAN CELL? It is essential to understand how the virus can get into the human cell and the consecutive effect of the virus in the body so we can have the opportunity to block it. An infected person can contaminate 2.6 other people through the droplets7. The nanoparticles of the virus form droplets and go to the hands and surfaces after an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even talk. Now the hands become a vector of disease as it carries the virus that can contaminate another person. That is already an advantage for us because we can always practice proper handwashing to effectively eliminate the virus.

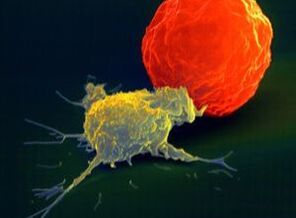

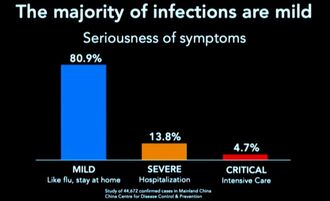

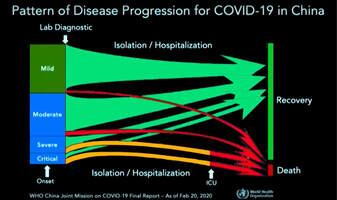

The virus takes advantage of the cell's machinery and uses it as the factory for viral replication. The virus is re-packaged, and then it sheds off the infected cell and propagate and eventually causes fibrosis in the lungs and leads to fatality9. HOW CAN WE STOP VIRAL PROPAGATION? In times of Pandemic where treatment is limited to alleviating symptoms, the only immediate solution is to have an effective immune response. It is also essential to understand that many people can get contaminated with any virus, but not all will get infected and end up with the disease. And that depends on multiple factors that include accessibility of virus to tissue, susceptibility to virus multiplication, the virulence of the virus, and the host immune response10. Our immune response depends on several biological and lifestyle factors that will be discussed in the next section. The immune system rests on two major pillars: the innate, general immune system and the adaptive, specialized immune system. Both systems work closely together and take on different tasks. The strength of the innate, general defense is to be able to take action very quickly. Because of this broad effect, it is only capable to a certain degree of stopping viruses from spreading in the body. Inflammatory cells move to the site of infection, and the complement system is activated, too, and helps to defend the body. This leads to an inflammatory reaction where blood circulation is increased and fever sets in. If the body’s first line of defense – the innate immune system – is unsuccessful in destroying the pathogens, the specific adaptive immune response sets in after about four to seven days. The adaptive immune system can remember the virus because it produces memory cells. This is also the reason why there are some illnesses you can only get once in your life because afterward, your body becomes “immune.”13. Take note of the two crucial immune cells that deal with viruses: The Natural killer cells (NK cells) and the Cytotoxic T-cell (T-killer cell). The NK cells are white blood cells (lymphocytes) that are aggressive first responders activated during a viral invasion. They specialize in identifying cells that are infected by a virus by looking for changes in cell surfaces. If natural killer cells find cells with a changed surface, they dissolve them using cell poisons, also called cytotoxins. They serve to contain viruses while the adaptive immune response generates antigen-specific Cytotoxic T cells that can clear the infection at a given period. It is essential to be familiar with the crucial key players in the immune response against viral infection. We need to know how to boost their function and avoid factors that may suppress their performance. The Natural killer cells are part of our Innate Immunity produced by the bone marrow and are found to be lodging in the lymph nodes, tonsils, and spleen. Whenever a virus comes in contact with human cells, the NK cells immediately take the first move. Unfortunately, the Coronavirus can stay in the body for more than thirty (30) days, and it can manage to find a way to evade the immune system and kill the Natural killer cells and the T-cell s in the body. As shown on data from China's experience, elderly patients who died of COVID-19 have low Natural killer cell and T-cell count7. However, it is well established that there is an age-associated decline of NK cell function responsible for many biological processes taking place during immune response8. Cigarette smoking also decreases the number and activity of NK cells in the lungs18. HOW TO RECOGNIZE AN INFECTION? Based on China's data, with over 44,000 cases, fever and dry cough are the hallmarks of the disease. This means that any person who develops fever and cough even without a test should suspect for infection and immediately proceed to self-quarantine to prevent potential contamination and infection spread. Signs and symptoms of COVID-19 also include body pains (myalgia/arthralgia), headache, difficulty of breathing, and diarrhea. Studies showed that 80.9% of infections are mild, 13.8% may go through severe infection, and 4.7% can develop critical condition7. Now we need to explore the known risks factors of advancing from mild to the critical stage of infection. RISK OF INFECTION & FATALITY AMONG INFECTED PERSON Any factors that disrupt Immune function makes a person at risk to contract an infection and eventually leads to fatal condition:

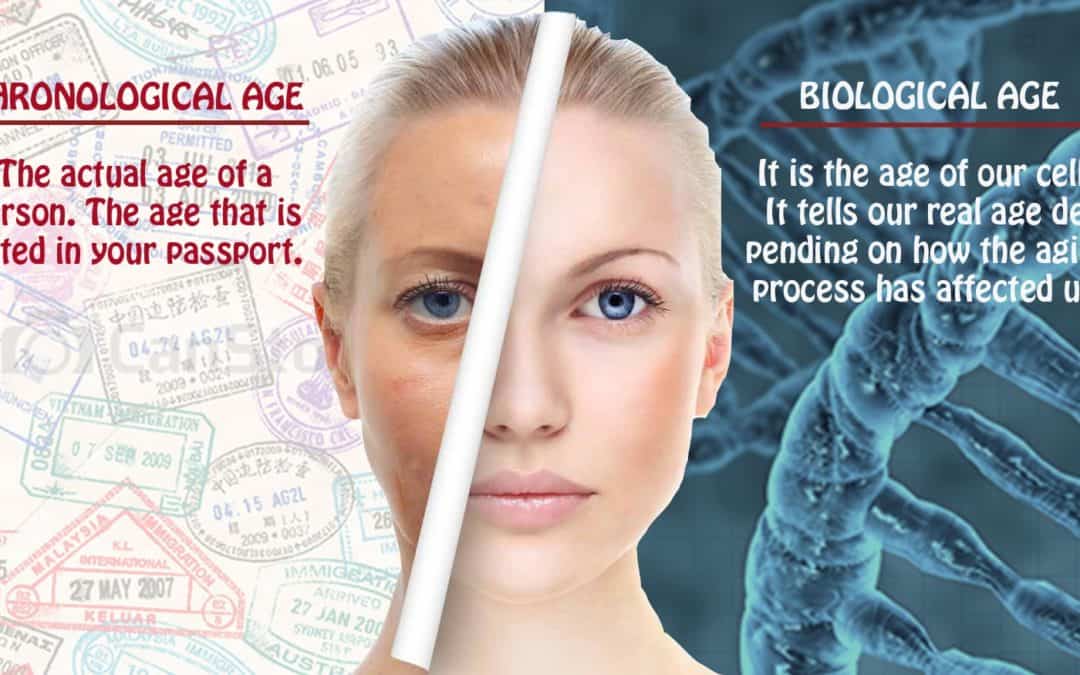

Aging and the immune System We all know the changes that occur as a person ages, and apparently, people age differently. Aging occurs at different levels of inquiry, biological, psychological, sociological, etc. All these levels address functioning, but from different viewpoints. This really means that the perceived age may vary from the actual chronological age, based on the usual presentation of individuals at a given calendar age. Performing as the first line of defense against COVID-19, natural killer (NK) cells as critical effector cells of the innate immune system is significantly impaired in elderly subjects. Such decreased NK cell activity has been shown to be associated with an increased incidence and severity of viral infection8. There is clear evidence that describes the state of profound age-associated changes in the immune system manifested by the overall decline of antigen-specific immunity. Lymphocytes are thought to have a finite replicative lifespan. Telomere length (tip of the chromosomes) may be the ultimate limit for the number of divisions that a human lymphocyte can undergo. Because telomeres are essential for maintaining chromosomal integrity, cells with critically shortened telomeres cease division (senescence) and are prone to die.

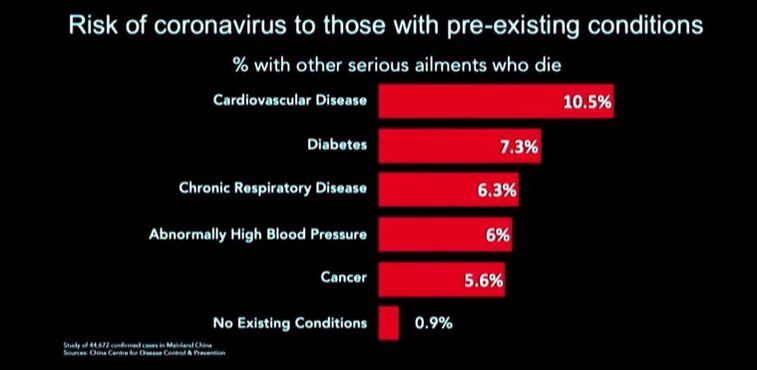

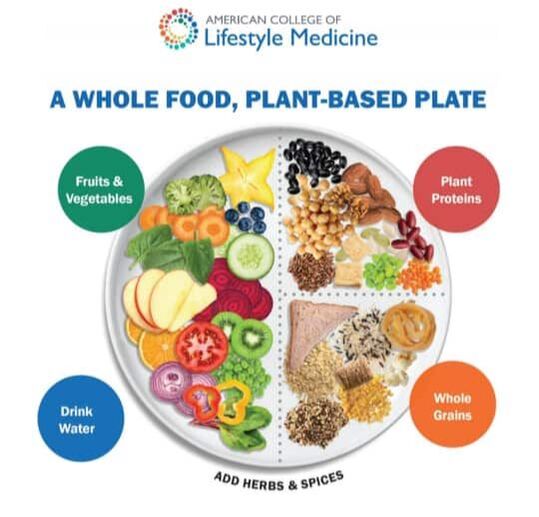

Aging is also associated with increased incidence of major diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, metabolic, and autoimmune diseases which are comorbid conditions that may render an older adult vulnerable to COVID-1912. But as we look at the current statistics around the world, chronic diseases, which are thought to be a disease of old age, are now affecting people at an early age. Their telomeres are also shortening, which diminishes the integrity of the cell. Aging is determined by lifestyle, dietary habits, mental makeup, and even environmental factors and genetic factors. Faulty dietary habits, lifestyle, and stressful living may wrongly influence one's biological aging, which is the sole indicator of health and age-associated diseases15. So a person may only be 45 by chronological age may already be 65 by biological age. Impaired Immune Response for COVID-19 due to Noncommunicable diseases Comorbidity is the presence of one or more additional conditions co-occurring with a primary condition. The data shown by China established that a person with comorbidity has the highest risk of getting infected and developing a fatal condition and dying of COVID-19. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, hypertension, and cancer documented pre-existing conditions of those who died during the disease outbreak7. Comorbidity is a known accurate predictor of impaired immunity than chronological age in adults. With increasing comorbidity in older adults, there is a proportional decrease in the immune response. The magnitude of impaired immunity depends on different specific illnesses and different levels of severity. It's not surprising to see healthy people aging 75 years old surviving COVID-19 while some 45 years old dying because of having underlying comorbidities20. The data clearly showed that the presence of Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) increases the risk of developing a fatal condition and eventually die when contracted with COVID-19. These chronic diseases are considered invisible epidemics that compose over 70% of the cause of mortality that is largely lifestyle-related and, therefore, preventable but under-appreciated23. Risk factors underlie the major NCDs are largely modifiable, including tobacco, harmful use of alcohol, unhealthy diet, insufficient physical activity, overweight/obesity, raised blood pressure, raised blood sugar, and raised cholesterol23. The long-standing NCD threat now also dictates the survival rate of persons infected with COVID-19. NCDs can be reduced using the existing evidence-based lifestyle intervention that offers highly proactive and cost-effective solutions. LIFESTYLE FACTORS THAT WILL BOOST ANTIVIRAL IMMUNE RESPONSE Adequate Sleep It is during sleep that repair and reversal of cell damage occur. Studies showed that alteration of immune function occurs even at a modest loss of sleep. The effect of early-night partial sleep deprivation is a reduction of natural immune responses on circulating numbers of white blood cells, natural killer cells, and cytotoxic T-cells. The killing activity of NK cells reduces by almost 30%. This implicates sleep in the modulation of immunity and demonstrates that even a modest disturbance of sleep reduces natural immune response, hence, subjecting the person to increased risk of viral infection1. In this generation, a huge percentage of people don’t meet the required number of sleep hours (7-8 hours) due to a wide variety of reasons. Exposing our eyes to Blue light suppresses the hormone MELATONIN, which is responsible for inducing sleep. The use of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) from electronic devices such as TVs, computers, smartphones, and tablets before bedtime may contribute to or exacerbate sleep problems. Exposure to blue-wavelength light, particularly these devices, may affect sleep by suppressing melatonin and causing neurophysiologic arousal17. Staying away from blue light spectrum exposure before the target time of sleep is necessary to achieve effective sleep. One proven way of improving sleep is to get good sunlight exposure in the morning. Daylight exposure could delay the sleep phase and correction of the circadian rhythm. Anxiety and insomnia could also be improved with daylight exposure with added activation of Vitamin D in the skin, which is also necessary to boost immune functionn16. The timing and amount of food intake at night were also found to affect the quality of sleep. Researchers at Brazil's Universidade Federal de São Paulo studied the relationship between food intake and sleep patterns in a group of healthy young adult men and women. They found that eating more heavily at night was associated with deterioration to several measurements of sleep quality. They also found that women were more vulnerable to the negative effects of nighttime eating on sleep. Having a light meal during dinner will greatly help attain good quality of sleep. Adequate Physical Activity Research showed that moderate physical activity might improve the function of immune cells. Moderate physical activity is specific for every person. You can tell when you are doing the moderate physical activity if you can no longer sing while doing your exercise. While regular exercise improves the natural immune response, following strenuous and exhaustive exercise will decrease the number of NK cells, and their activity is depressed for several days. On the other hand, Sedentary behavior, characterized by a sitting or reclining posture and low-energy expenditure, has been recognized as an independent health risk factor. Evidence shows that being sedentary is associated with an elevated risk of insomnia and sleep disturbance and ultimately affects the immune response2. Regular physical activity should be matched with the age and the capacity of an individual to move. There are a variety of ways to increase physical activity, even during periods of self-quarantine or isolation. Seated exercises and stationary walking are some very common examples of activities that anyone can do with the help of available online instructional videos. Exercise causes the heart to pump blood into the circulation more efficiently, resulting in increased oxygen delivery and increased perfusion of tissues and organs with blood components, including the immune cells. Right Food Combination for Nutritional Immunology A well-functioning immune system is critical for survival. It should be constantly alert in monitoring for signs of invasion by distinguishing self from non-self and discriminating against harmful molecules like pathogens. A well-balanced whole food plant-based diet (WFPB) enhances immune function in contrast with meat and refined carbohydrates. It is imperative to have a better understanding of the role of diet and nutrients in immune function. Adequate and appropriate nutrition is required for optimal function of "activated" immune cells, allowing them to initiate effective responses against pathogens, increasing the basal energy expenditure during infection periods. High resveratrol intake on a regular basis was also noted to have immunomodulatory properties. These can be found in plant-based sources such as peanuts, grapes, soy, and berries. Avoiding sugary food and beverage is also extremely important to prevent suppression of immune response. Alcohol and smoking also increase one's risk for viral infection2. Avoiding processed food, meat products, and refined carbohydrates are known causes of gut microbiome disruption or dysbiosis that will alter immune homeostasis. Remember that our gut wall houses 70% of the cells that make up our immune system. So the gastrointestinal system plays a central role in our immune system homeostasis. It is the main route of contact with the external environment and can be overloaded every day with pathogens or toxic substances3. Consuming naturally prepared whole-food plant-based meals will significantly change the composition of the gut microbiome in favor of a positive immune response.

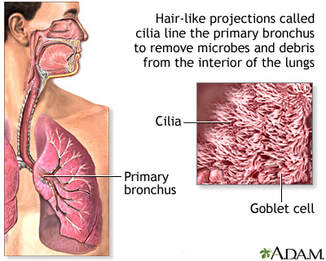

The Power of Positive Mental Attitude Studies have shown that stress and depression reduce NK cells and T-killer cells' ability to respond to viral infection. However, positive thinking and problem-solving coping skills can improve NK cells activity even in stressed individuals. Regular exercise is thought to be associated with stress reduction and better mood, which may partly mediate associations between depression, stress, and health outcomes and its potential role of the inflammatory response as a central mechanism. Psychosocial factors, such as chronic mental stress and mood, are significant predictors of longevity and well-being. In particular, depression is independently associated with cardiovascular disease all-cause mortality, diabetes, obesity and is often comorbid with chronic diseases that can worsen their associated health outcomes4. While people face fear, stress, and uncertain lifestyle adjustments due to the current crisis, We are seemingly left with only one choice: to protect ourselves through boosting immune response. Think about Neuroplasticity, the ability of our brain to recognize itself in response to situations and changes in the environment. We can always choose to create a new Neurological pathway leading to a Healthy Lifestyle instead. Quit Cigarette Smoking and Avoid Alcohol Aside from compromising the respiratory cilia, smoking impacts both innate and adaptive immunity and plays dual roles in regulating immunity by either exacerbation of pathogenic immune responses or attenuation of defensive immunity. Smoking also plays a complex role in numerous diseases, including cardiovascular, respiratory, and autoimmune diseases, allergies, and cancers21 These are known comorbidities that increase the risk of a person contracting a viral infection and eventually developing a fatal condition. There is no other way to go but to deliberately quit smoking with the help of your health care provider if needed so. Alcohol disrupts immune pathways in complex ways. These disruptions can impair the body’s ability to defend against infection, contribute to alcohol’s combined effects on innate and adaptive immunity, significantly weakening host defenses, and predisposing chronic drinkers to a wide range of health problems, including infections and systemic inflammation. Alcohol also interferes with the developing immune system in the fetus, and this exposure increases a newborn’s risk of infection and disease deleterious effects on immune development last into adulthood. Alcohol also alters the composition of the gut microbiome, an extensive community of beneficial microorganisms in the intestine that aid in normal gut function. These organisms affect the maturation and function of the immune system. Alcohol disrupts communication between these organisms and the immune cells with essential implications beyond the intestinal immune system. Alcohol disrupts ciliary function in the upper airways, impairs the function of immune cells, and weakens the barrier function of the epithelia in the lower airways. Studies showed that alcohol-provoked lung damage often goes undetected until a second insult, such as a respiratory infection, and leads to more severe lung diseases than those seen in nondrinkers22. PROACTIVE AND PREVENTIVE APPROACH Just like the way we think about any other mainstay and seasonal viruses we co-exist with, ROBUST IMMUNE RESPONSE is always associated with self-limited clinical recovery. But due to our modern LIFESTYLE, we are exposing ourselves to many various factors that don't favor boosting our immune system at all. Just when we thought that it's mostly Noncommunicable diseases that will be impacted by LIFESTYLE MEDICINE, experts are now starting to realize and appreciate more than ever that our NATURAL IMMUNE RESPONSE which largely depends on HEALTHY BEHAVIORS is the first line of intervention in the level of Prevention, Management and Recovery from Communicable diseases. This is specifically true for a new type of viral disease where ample time is needed to create immunization or a pill that will only mimic the weapon naturally used by our immune system. Indeed, the hardest battle is fighting with the unseen, not just the COVID-19 but mostly the battle between so many choices and habits that became part of our modern lifestyle. The good news is that we can always initiate a behavior change and reorganize to finally lead us to live an OPTIMAL LIFESTYLE that will not only shield us from infectious disease but mostly from a non-communicable disease that is taking over a thousand lives of Filipinos every single day. Learn and Share References:

1. Irwin M, McClintick J, Costlow C, Fortner M, White J, Gillin JC. Partial night sleep deprivation reduces natural killer and cellular immune responses in humans. FASEB J. 1996 Apr;10(5):643-53. PubMed PMID: 8621064. 2. BioMed Centra. "ALcohol impairs the body's ability to fight off viral infection, study finds." ScienceDaily, 2 October 2011. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/09/110929235156.htm 3. Yang Y, Shin JC, Li D, An R. Sedentary Behavior and Sleep Problems: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2017 Aug;24(4):481-492. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9609-0. Review. PubMed PMID: 27830446. 4. Vighi, G., Marcucci, F., Sensi, L., Di Cara, G., & Frati, F. (2008). Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clinical and experimental immunology, 153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03713.x Hamer M, 5. Endrighi R, Poole L. Physical activity, stress reduction, and mood: insight into immunological mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;934:89-102. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-071-7_5. PubMed PMID: 22933142. 6. Naming Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) and the virus that cause it. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. 7. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report. 8. Hazeldine, Jon, and Janet M Lord. “The impact of ageing on natural killer cell function and potential consequences for health in older adults.” Ageing research reviews vol. 12,4 (2013): 1069-78. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2013.04.003 9. The American Journal of Pathology. "Pathology and Pathogenesis of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome." https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1829448. 10. Samuel Baron, Michael Fons, and Thomas Albrecht. Medical Microbiology. "Viral Pathogenesis". Chapter 45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8149. 11. Jazwinski SM, Kim S. Examination of the Dimensions of Biological Age. Front Genet. 2019;10:263. Published 2019 Mar 26. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00263. 12. Gian Andrea Rollandi 1, Aldo Chiesa 1, Nicoletta Sacchi 1, Mauro Castagnetta 1, Matteo Puntoni 1, Adriana Amaro 2, Barbara Banelli 2, Ulrich Pfeffer 2.OBM Geriatrics. Biological Age versus Chronological Age in the Prevention of Age Associated Diseases. 13. Aoshi T1, Koyama S, Kobiyama K, Akira S, Ishii KJ.Innate and Adaptive Immune Response to Viral Infection and Vaccination. Curr Opin Virol. 2011 Oct;1(4):226-32. PubMed PMID: 22440781. 14. Weng NP. Aging of the immune system: how much can the adaptive immune system adapt?. Immunity. 2006;24(5):495–499. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.001. 15. Samarakoon SM, Chandola HM, Ravishankar B. Effect of dietary, social, and lifestyle determinants of accelerated aging and its common clinical presentation: A survey study. Ayu. 2011;32(3):315–321. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.93906. 16. Karami Z, Golmohammadi R, Heidaripahlavian A, Poorolajal J, Heidarimoghadam R. Effect of Daylight on Melatonin and Subjective General Health Factors in Elderly People. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(5):636–643. 17. Tosini, Gianluca et al. “Effects of blue light on the circadian system and eye physiology.” Molecular vision vol. 22 61-72. 24 Jan. 2016. 18. Hervier B, Russick J, Cremer I, Vieillard V. NK Cells in the Human Lungs. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1263. Published 2019 Jun 4. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01263. 19. Shammas MA. Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(1):28–34. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834121b1. 20. Castle SC, Uyemura K, Rafi A, Akande O, Makinodan T. Comorbidity is better predictor of impaired immunity than chronological age in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Sep;53(9):1565-9. PMID:16137288 21. Qiu F, Liang CL, Liu H, et al. Impacts of cigarette smoking on immune responsiveness: Up and down or upside down?. Oncotarget. 2017;8(1):268–284. doi:10.18632/oncotarget. 13613. 22. Sarkar, Dipak et al. “Alcohol and the Immune System.” Alcohol Research : Current Reviews vol. 37,2 (2015): 153–155. 23. World health Organization, 2014. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World health Organization. |

AuthorMechelle Acero Palma, MD Archives

August 2021

Categories |

|

Working Hours

Monday to Friday: 8:00am to 5:00pm Online course: 24/7 |

The Philippine College of Lifestyle Medicine is an Affiliate Specialty Society of the Philippine Medical Association under the division of the Philippine Academy of Family Physicians

RSS Feed

RSS Feed